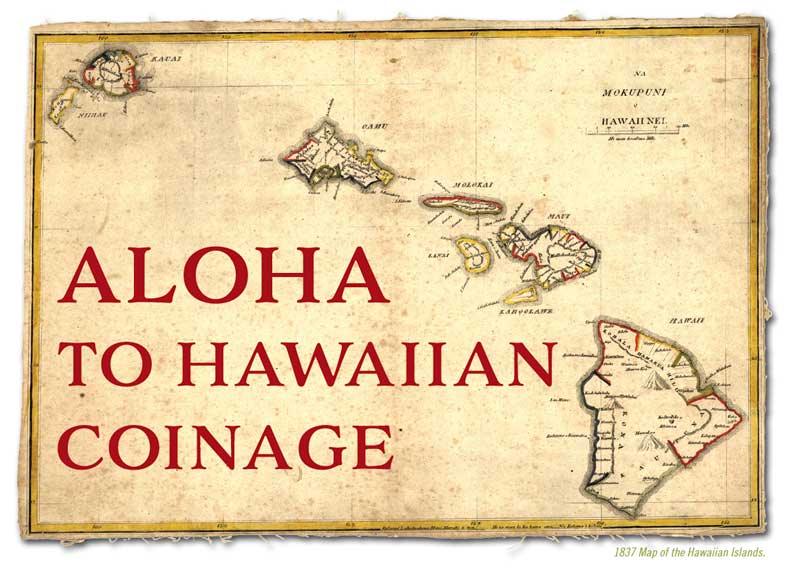

Aloha to Hawaiian Coinage

The coins struck in Hawaii from 1847 to 1883 represent a truly unique and highly collectible area of the U.S. rare coin market. Some coins are surprisingly affordable and quite rich in history. Mike Garofalo reviews this area in depth with a great perspective for the dealer and collector alike.

An 1847 Hawaiian Keneta Cent.

Nearly 2,500 miles to the southeast, off of the coast of California, lay the Hawaiian Islands. Hawaii is a group of eight islands and it is believed that they were first settled sometime between 300 to 600 AD by Polynesians from the Marquesas Islands.

The history of the Hawaiian Islands, in many respects, has similarities to that of the United States. Just as Italian explorer Christopher Columbus “discovered” America, much to the chagrin of the native peoples already living there, British explorer, Captain James Cook “discovered” the Hawaiian Islands, much to the chagrin of the indigenous Hawaiians already living there and who may have been there for more than 1,000 years prior. Cook promptly renamed them the Sandwich Islands after the Earl of Sandwich, but that name disappeared in the 1840s, replaced by the Hawaiian Islands.

[View Greysheet & CPG pricing for Hawaiian coinage]

But just as America had no native coins or currency when the European settlers began to move there, neither did Hawaii in their earliest of days. Bartering was commonplace in the early colonies but with people coming from different countries and bringing their valuables with them, American trade using coins began to flourish, by using British Sovereigns, Dutch Guilders, Spanish Escudos and other coinage.

A WORKABLE COINAGE

Likewise, as British sailors came to and settled in Hawaii, the use of British coinage and denominations began to dominate trade there as well. But items such as Cowry shells, certain types of feathers and later, sandalwood are all reported to have been used as exchange before the British had landed there and also later, when foreign coinage was in short supply.

The Pattern 1881 Five Cent Piece of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

LOCAL COINAGE

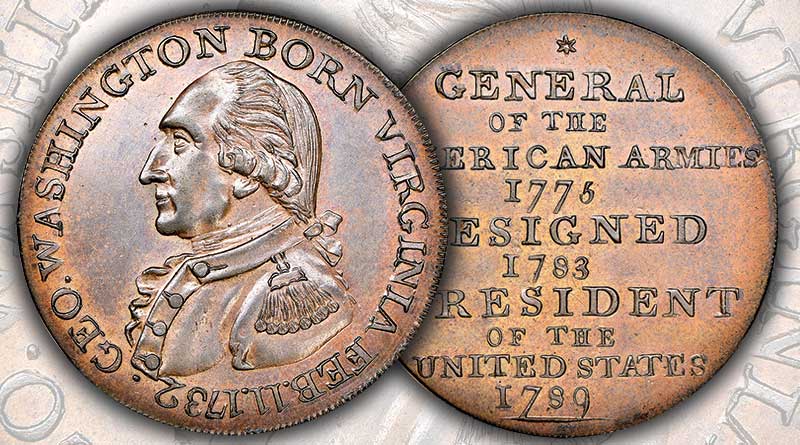

King Kamehameha I served as first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Although numerous dates have been offered, the accepted year of his birth was around 1736. His mother was the niece of the usurping ruler of Hawaii at that time and he was adopted as his infant son and heir. King Kamehameha I was the first ruler to recognize the value of gold and silver coinage as money. One of his sons, King Kamehameha III, who succeeded him, wanted to establish a local coinage as opposed to using foreign coinage.

Kamehameha III established a monetary system for use in Hawaii and he tied it to the US dollar and coinage. He created a “Keneta”—a one cent coin much like a US large cent. The King’s plan was to have a large quantity of this low denomination coin minted and once they were acceptable to the Hawaiian population to introduce several larger denominations.

The Keneta is roughly the same diameter as the Large Cent. The obverse bears a military bust of the king on the obverse, facing front, with the legend “KAMEHAMEHA III. KA MOI.” around him and the date “1847” below. The reverse has the denomination “HAPA HANERI” within a wreath, tied with a bow at bottom, surrounded by “AUPUNI HAWAII.” There are two different obverse varieties—one with a Plain 4 in the date, and the other has a Crosslet 4. There are also six separate varieties of reverse dies.

It was agreed that 100,000 of these Keneta coins would be struck by H.M & E. I. Richards of Attleboro, MA. This company had struck a number of Hard Times tokens so they were respected private minters.

The 1883 Hawaiian dollar coin.

The coins left the port of Boston on the merchant ship S.S. Montreal. The journey would leave Boston, sailing south down the eastern coast of America, south past Central America and skirt the east coast of South America. The ship made a planned stop at Rio de Janeiro and then sailed south coming around the tip of South America at Tierra del Fuego. Now the Montreal headed north along the coast of South America and then at Santiago, Chile, headed due west across the Pacific to Tahiti. That was the last stop before docking in Honolulu. But after five months on board the humid and wet ship, many of the copper coins were badly discolored.

But that was not the worst discovery. The King’s portrait was very disappointing as he was unrecognizable to his subjects. This certainly set these coins off on the wrong trajectory. It took a number of years before even a small number of the 100,000 coins were disbursed. More than 88,305 coins were eventually shipped out of Hawaii and scrapped. The Keneta experiment was not a rousing success then but today the coins are considered scarce and are valuable.

But the next coinage experiment would not occur for 34 years. In 1881, then-King Kalakaua was traveling throughout Europe and was approached by French Mint officials who convinced the King that the Kingdom of Hawaii required its own coinage to truly be a sovereign nation. The King was convinced and ordered 200 pattern Five Cent coins to be struck and shipped to him. Interestingly, he allowed the English name “Sandwich Islands” to be utilized on the obverse.

The 1883 Hawaiian Half Dollar coin.

The obverse would have a bust of the king facing left and “KALAKAUA KING OF SANDWICH ISLANDS” surmounting the King and the date “1881” below him. The reverse would display the Crown of Hawaii and the long Hawaiian Motto encircling the numeral “5”. But here again an engraver’s mistake incorrectly spelled the first word in the Hawaiian Motto “UA” as “AU” and when that was discovered, the coins were rejected out of hand.

King Kalakaua was not deterred by the Five Cent fiasco. Although American coins were circulating throughout the Islands, the King truly wanted the Kingdom to have its own coinage. This time the King turned to a trusted friend of his, Claus Spreckels, to negotiate and mediate negotiations between the Kingdom and the United States Mint. The Hawaiian Coinage Law passed in 1880 provided for a One Dollar, a Fifty cent, a Twenty Five cent, and a Twelve-and-One-Half cent coins. However, to be compatible with US coinage the Twelve-and-One-Half cent coin was changed to a Ten cent coin.

Spreckels began corresponding with the Director of the US Mint, Horatio Burchard. Burchard advised him that the US Mint would strike coinage for Hawaii but the dies would need to be engraved in Philadelphia and after they were approved, the dies would be sent to San Francisco for minting. He asked Spreckels to provide him with sketches of the King, whose portrait would grace the obverse of all denominations of coins. The sketches were received and rejected by Charles E. Barber, the Chief Engraver of the US Mint, as they were full face. After additional negotiations, Spreckels was able to provide profile sketches as they would be compatible with US and other world coinage designs in that manner. After approval, Barber sent dies to San Francisco for striking.

The 1883 Hawaiian Quarter Dollar coin.

The One Dollar coin depicted a bust of King Kalakaua facing right. Above him are his name and “KING OF HAWAII”. The date, “1883”, which is below his bust is offset with two periods, one on either side of the date. The reverse displays the shield of the Royal Arms, emblazoned on a mantle, on the Dollar coin. Above the shield is the Royal Crown as well as the Star of Kamehameha, suspended below the shield. Surmounting the shield is the motto of Hawaii and the denomination in English “1 D” is below the motto and the denomination in Hawaiian is provided at the bottom of the coin—“AKAHI DALA.” The complete mintage of Silver Dollars, 500,000 coins were struck at San Francisco.

The next coin struck was the Hawaiian Fifty cent piece. 700,000 of those coins were struck and shipped to the Kingdom. The obverse design was the same, other than the size was reduced. The reverse was changed as to simply display the Royal Arms with the Crown above it. These elements are not displayed on the previous mantle nor is the Star of Kamehameha shown at all. The denomination is displayed as “1/2 D” in English and also in Hawaiian as “HAPALUA”.

The Mint struck 500,000 Hawaiian Quarter Dollars and the design exactly matched that of the Half Dollar, except in size and in the denomination expressed on the reverse as “1/4 D” in English and as “HAPAHA” in Hawaiian.

[View Greysheet & CPG pricing for Hawaiian coinage]

The Proof 1883 Hawaiian 12.5 cents (1/8 dollar) Pattern coin.

Although the Mint struck 26 Proof examples of each of the four major denominations, they also struck 20 Proof specimens of the Twelve and a Half Cents coins. The coins had a unique reverse in that the Motto of Hawaii surmounted the design. The Royal Crown was below the motto but not inside the wreath. Inside the wreath was the Hawaiian denomination “HAPAWALU” and at the bottom of the coin was “EIGHTH DOL.” These Proof coins were intended for Members of Congress, Hawaiian officials and members of the royal family. No proof One Cent coins were issued or struck.

Finally, for the Hawaiian Ten Cent coin, the US Mint had 250,000 coins struck. It mimicked the design of the 12 ½ Cent coin, except for the denomination “ONE DIME” inside of the wreath and the Hawaiian version “UMI KENETA” at the bottom. It bore a very close resemblance to the Barber Dime of the day.

ACCEPTED BUT SHORT-LIVED

With all of this new coinage circulating through the islands, the foreign silver coins were essentially exchanged out of circulation for the desirable Hawaiian coinage. By the end of the 1880s, Hawaiian coinage had even replaced US coins, which had been the most wanted coinage for the last two decades.

The 1883 Hawaiian Dime.

By the 1890s the Hawaiian population, led by foreign residents and some US citizens, was displeased with the monarchy and it finally fell. The Islands declared their autonomy as a Republic on July 4, 1894. Yet during that period the coinage, even while bearing portraits of prior monarchs, remained the symbol of stability. But by 1898, the Republic of Hawaii was no more and it was annexed by the United States as an Official Territory.

In 1903, Congress decreed that as of January 1, 1904, all Hawaiian silver coinage had to be exchanged for U.S. coinage. When that was completed, nearly $814,000 of the original $1,000,000 face value of Hawaiian coinage had been returned to the United States Mint in San Francisco and melted and remanufactured into U.S. coins. Less than $190,000 worth of face value Hawaiian coinage remained in existence.

The Proof Hawaiian coins that exist today are exceptionally rare and usually are sold at major auctions or by private treaty by a major dealer to an important collector. The Hawaiian proof coinage that was in the Garrett Collection, including a Proof Dime, Proof Dollar and a Proof Pattern Dollar, were all sold for the benefit of Johns Hopkins University in 1981 and they brought record prices at the time.

THE PLANTATION TOKENS

1855-1860 John Thomas Waterhouse Plantation Token.

Hawaii’s main crop has always been sugar cane and the Islands’ main export caused very large plantations to be created on virtually all of the islands. Like most agrarian economies, when coinage is not available, the plantations, themselves, will create ‘money’ that can be used as cash within the company stores that sprang up. Many of these Hawaiian tokens are well-known and widely collected today.

One of the earliest plantation tokens is the (circa 1855—1860) John Thomas Waterhouse Token. It was struck in white metal, a metallic compound similar to pewter. J. T. Waterhouse was founded in 1851 and the company still survives today.

Waterhouse had an unknown number of tokens struck to be used in their own company store on the grounds of their plantation. The token’s obverse displays a full facing bust of King Kamehameha III, but the surrounding legends on the token incorrectly describe him as “HIS MAJESTY KING KAMEHAMEHA IV.” The reverse of the token displays a beehive, representing industry, with the issuer’s name above “JOHN THOMAS WATERHOUSE IMPORTER” and the Hawaiian expression “HALE MAIKAI” meaning house excellent (i.e., a good place to do business) at the bottom.

1871 Wailuku Plantation Token in 12.5-cent denomination.

A number of the other plantation tokens were much less sophisticated in their design but were the popular coins of the realm for those working on these plantations. A very popular denomination for a number of these plantation tokens is Twelve and a Half Cents, as that is what many workers were paid for a full twelve hours of back-breaking daily labor.

The Wailuku Plantation issued two simple but effective tokens in both 12.5 cents and 6.25 cents denominations for full day and half day labors. They also issued tokens One Half Real and One Real.

The Thomas H. Hobron Plantation issued 12.5 cents and 25 cents tokens in 1879 for use in their plantation stores. The tokens were again made of copper but were better struck and less crude.

Additionally, tokens were struck in very limited quantities for the Grove Ranch Plantation and in numerous denominations, but in limited numbers, for the Kahului Railroad as transportation fares. All of these tokens represent an opportunity to collect Hawaiian mediums of exchange, during a period when the country grew but had no established monetary system.

COLLECTING HAWAIIAN COINAGE–YESTERDAY AND TODAY

I have a mainlander’s view of Hawaiian coinage, since I have been purchasing it and selling it for over four decades. But to get a different perspective I spoke with Craig Watanabe. Craig is President of Captain Cook Coin Company of Honolulu. He has been in business for more than 50 years. Craig has seen many changes to both the coin hobby in general, and to Hawaiian coinage in particular.

1879 Thomas Hobron Token in 12.5 cent denomination.

Craig commented as follows, “Between the 1960s and about 1990, many Hawaiian coin dealers, including myself, actively promoted Hawaiian coinage and offered Buying and Selling Prices to the public. But with the onset of the grading services many Hawaiian coins and tokens were upgradeable as a good number of them had been cleaned. I learned that the true collectors wanted one of each denomination of Hawaiian coinage. Having the history of these coins in the Red Book (A Guide Book of United States Coins—Whitman Publishing) and now having current pricing in the Coin Dealer Newsletter has greatly helped collectors and dealers formulate their own pricing and collecting strategies. I feel that much of the surviving mintage of Hawaiian coins is still in Hawaii. But many of these coins have been cleaned and especially the 1847 Cents as the climate of Hawaii is unfriendly to copper,” Watanabe concluded.

I agree with many of Craig’s comments but my experience has shown me that Hawaii, California, and other West Coast dealers are more likely to have Hawaiian coinage in their inventory than East Coast dealers. Many of the surviving, uncleaned, high-grade specimens already reside in PCGS or NGC holders.

My advice to a collector today is to look for uncleaned coins with attractive toning or ones with eye-appeal and whether they have been certified or not, to seriously consider them if they are priced near these current levels. The surviving numbers of available coins are low and finding these historic coins, priced near Greysheet levels, seems like a smart purchase over the long-term. Aloha!

(All images in this article are courtesy of Heritage Auctions. www.ha.com)

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to Monthly Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Michael Garofalo