A Brief History Of James B. Longacre's One Dollar Gold Coins, Part 2

An overview of how the gold dollar originated and evolved in the mid-1800s.

The Coinage Act of 1792 envisioned that a minting facility was required to be built as well as outlining the key roles at the mint that needed to be filled. It also determined the denomination of coins that the fledgling United States would need in order to conduct domestic and international commerce, as a true and independent country. While the Act required a One Dollar coin, it made no reference as to whether that coin must be comprised out of gold or silver. Between 1794 and 1848, all dollar coins were made only from silver.

The history of the One Dollar gold coin truly began with the discovery of gold in California. Prior to that 1848 event, there had been gold discoveries in both Georgia and North Carolina but neither of these events required a One Dollar gold coin to be struck. The Seated Liberty Silver Dollar and its predecessors handled the job quite nicely.

James Barton Longacre, the Chief Engraver of the United States Mint, designed a small gold coin that was first struck in 1849. That particular coin was plagued with problems and only lasted until 1854. There were a tremendous number of complaints about the exceedingly small diameter (13 mm) of that first effort. Coins that small and very thin could easily be lost and when that loss represented a day’s wages, it was a problem that could not be ignored.

Longacre redesigned the coin in 1854, and the diameter was increased by 15%, from 13mm to 15mm. This was the new Type Two coin design. While that alone was an improvement, the problems were not over. Now the issue was not size, but the strike. Longacre’s new design was sculpted in significantly higher relief than the earlier Type One coins. Now the coins did not strike well as parts of the design were now barely legible, That proved totally unsatisfactory as well.

So in 1856, a third design was offered by Longacre to the American public. His design was similar to the Type Two design in that this coin depicted Miss Liberty wearing a Native American headdress, facing to the left. Much like the prior design, it also displayed the motto “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,” around the periphery. Miss Liberty retained the word “LIBERTY,” on the crown of her headdress. In fact, her head was enlarged over the Type Two coin. Her hair was arranged in a different position and her headdress was positioned higher and more upright. The relief of this new Type Three design was significantly lowered. This was not done for aesthetic appeal. It was done in order to reduce the number of places where recessed areas in the dies were exactly opposite one another. That would allow for the metal to flow more evenly between the dies and permit the coins to have a better and fuller strike.

The relief on the reverse was lowered as well, but there are no other noticeable design changes on the reverse. The wreath of comprised of corn, cotton, tobacco, and wheat remained, along, with the numeral “1” and the word “DOLLAR,” in two lines inside the wreath. The date still displayed inside the wreath as well and the usual bow tying the wreath together also remained.

Both the Type Two Gold Dollar (1854 to 1856) and the Type Three Gold Dollar (1856 to 1889) are sometimes referred to as the “INDIAN PRINCESS” heads, with Type Two being identified as the “SMALL HEAD,” and the Type Three as the “LARGE HEAD.”

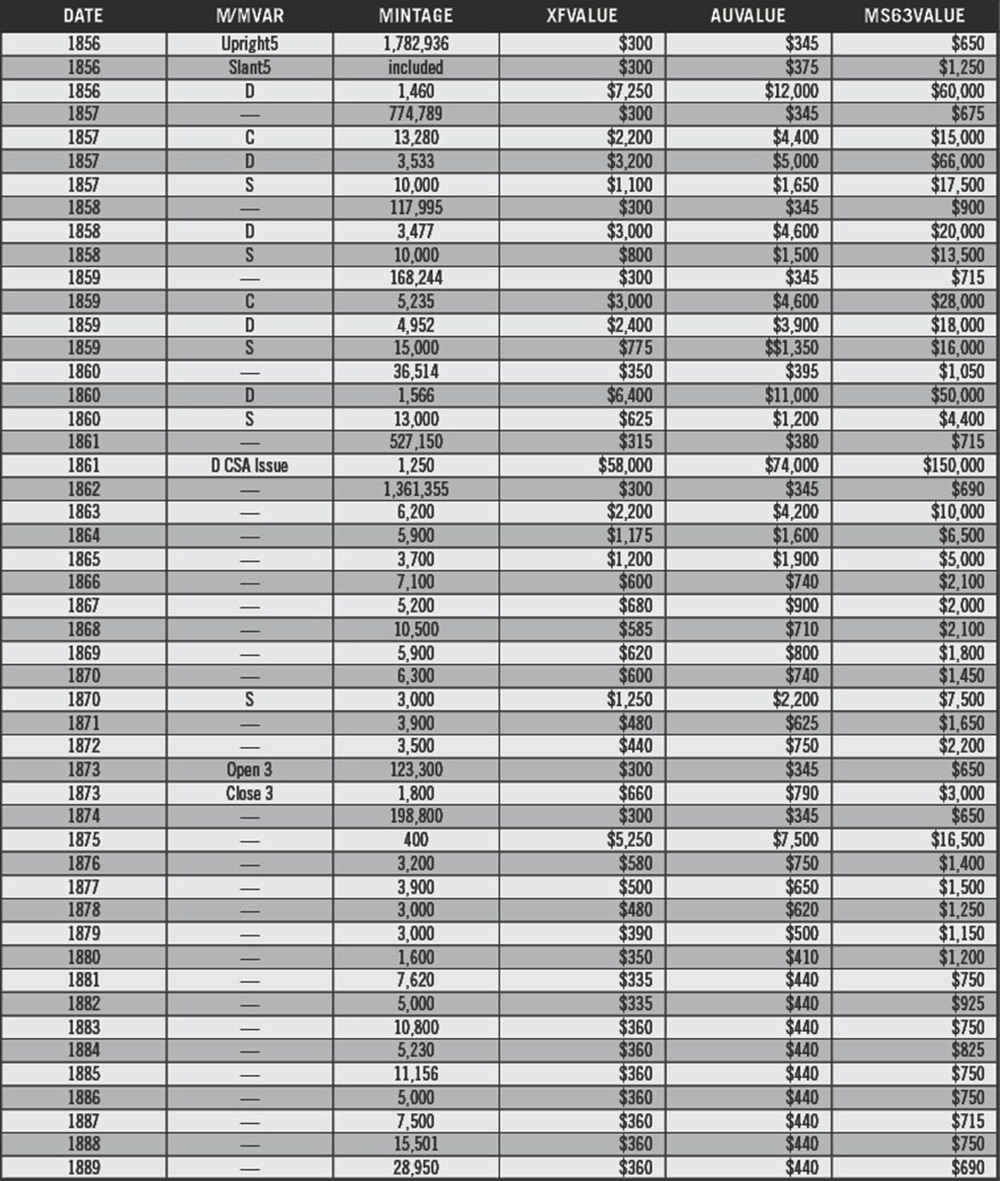

The coins struck at the Philadelphia Mint during the inaugural year of 1856 have the highest mintage of the entire series of 1,762,936 pieces. But those coins are divided into two major varieties—Upright “5” and Slanted “5.” That pertains to the positioning of the “5” in the date. The coins are valued similarly in price until the coins are in Mint State grades, where the Upright 5 variety becomes significantly more valuable.

While no one knows for certain how many coins of each type were struck, the rarity values are based, in part, on the numbers of coins certified of each type. Additionally, there are also incomplete mint records of how many coins were struck each month. Unfortunately, the mint generally made very few, if any, notations of die changes for each type of coin.

Coins were now being struck at the Philadelphia, Dahlonega, Charlotte, and the newly-opened San Francisco mint. However, the coins struck at all of the branch mints were in very low quantities. The branch mints continued to have many more issues with striking that the Philadelphia mint had.

1859 became the last year that all four mints struck these coins. 1860 saw no gold dollars struck at the Charlotte mint, but that branch mint did strike $2.50 gold quarter eagles and $5.00 gold half eagles instead.

But 1861 proved to be a watershed year for these coins, and for our country as well. Several southern states had begun to secede from the Union, starting a few months earlier in December of 1860. People in those southern states, especially slave-holders and those sympathetic to that cause, were alarmed by the election of Abraham Lincoln in November. It wasn’t long before North Carolina, Louisiana, and Georgia all followed suit. Georgia was fifth state to secede, which occurred on January 19, 1861. Louisiana was the sixth to leave, happening on January 26, 1861. North Carolina was tenth state to secede, which occurred on May 20, 1861.

The succession of those states posed serious problems for the employees of the Dahlonega, New Orleans, and Charlotte Mints. For the Dahlonega Mint, two pairs of 1861-D coin dies for the One Dollar gold coin had arrived at their facility on January 7, 1861. Due to the prevailing sentiment across the state of Georgia, it appeared that should the federal government request the dies to be returned or used to strike coins, both requests would be denied.

Once Georgia seceded on January 19th, all communications with the U.S. government were curtailed. The Governor of Georgia, Joseph E. Brown, was now in charge of the Dahlonega Mint. Troops from the Confederate States of America seized the mint on April 8, 1861. The Dahlonega Mint Superintendent, George Kellogg reluctantly surrendered to them, and he sent a letter to President Lincoln advising him of that fact.

All of the employees now had to swear allegiance to the Confederate States of America. Confiscated were all of its equipment, including the coinage dies, and approximately $13,345 worth of gold bullion which was supposed to be minted into U.S. gold coins.

The Confederate States of America still planned to strike 1861-D gold dollars, but instead of being shipped north to Philadelphia or Washington, they would be used to benefit the Confederacy.

As a few of the employees did not continue at the Mint, they were replaced by willing amateur minters, which explains why these coin planchets from the Dahlonega Mint were sometimes rough and uneven. This is the only American circulating coin that was struck in its entirety by the Confederate States of America.

On these 1861-D coins, the obverse die that was selected to strike these coins had been used to previously strike the 1860-D One Dollar gold coins. But while as many as 1,250 coins may have been struck, it is estimated that only 60 to 75 coins may actually exist today. The staff at the Mint also struck 1,597 1861-D $5.00 Gold Half Eagles.

The 1861-D was the last gold dollar struck at the Dahlonega Mint. In fact, no other branch mint gold dollars were again struck until 1870, when the San Francisco Mint struck 3,000 gold dollars.

In 1862, the Philadelphia Mint struck 1,361,355 coins and through the end of production in 1889, only twice more would quantities of 100,000 or more coins be struck, in 1873 and in 1874. 1873 would also see two major varieties—an Open 3 and a Closed 3.

In 1875, the production fell to its lowest number in the coin’s history, as only 400 coins were struck. The series continued to be struck annually through 1889.

In the late 1870s, these small gold dollars faced fierce competition of the newly struck and very popular Morgan Silver Dollar. Big, heavy, and containing over three-quarters of a Troy Ounce of pure silver, the new silver dollars had little competition in the marketplace. Additionally, the fact that the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 mandated that the Treasury had to purchase at least $2 million worth of silver every month from the western mining interests.

In assessing the collectability of these Type 3 coins, the toughest dates are the 1856-D, 1859-C, 1860-D, 1861-D and the 1875 extremely low mintage rarity. Beyond those five coins, there are few stoppers in putting together a nice, nearly complete set of Type Three Gold Dollars.

It is hard to imagine that a nearly complete set of One Dollar gold coins, assembled by the well-known Philadelphia coin dealer, Henry Chapman, was unknown until recently.

It had been stored in safe deposit boxes in a Philadelphia bank vault for more than a century. The collection contained 51 of the Type One, Two, and Three gold dollars. The coins were recently graded by PCGS, and this set includes many of the finest known certified examples.

The genesis of the set began in 1899, assembled for a Philadelphia banking family by Chapman. Each coin was housed in their original paper envelopes imprinted with Chapman’s business name. The coins remained in their safe deposit boxes for more than a century, until recently discovered. With some of the coins being the finest known or close to that, who knows what other collections still exist, undisturbed.

This proves the old adage that ‘not every great collection has already been discovered.’

Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions & Wikimedia.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Michael Garofalo

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

When the United States took control of the Philippines, Congress enacted the Philippine Coinage Act of 1903 which established a new currency system based on the United States gold standard.

Weinman did not consider himself to be a coin designer or medalist, but instead referred to himself as a sculptural artist.

This earliest half dimes have been the subject of more than two centuries of rumors, innuendo, and conjecture.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments