Bison On Coins & Currency: Where the Buffalo Roam in Numismatics

Collecting Buffalo nickels can be rewarding and fun. This series is easily one of the most popular among all collectors of U.S. coins.

In numismatics, lore surrounding the models who are linked to obverse portraits seen on Draped Bust coinage, the Indian Head cent, Morgan dollar, and other coins could fill volumes. But along with the human figures whose names are forever tied to the familiar faces seen on many of our coinage are creatures great and small that served as muses for some of the nation’s greatest coin designers.

The bison appears on this popular 1901 $10 Legal Tender note.

Among these are Peter, the Mint Eagle – an historic Philadelphia superstar whose fame is perhaps eclipsed only by “Rocky” (Sylvester Stallone) and actor Will Smith. Tradition has it that sometime in the 1830s, Peter flew the blue skies of Philadelphia by day and at night roosted at the United States Mint. Misfortune struck poor Peter, who was accidentally caught in the flywheel of a mint press, and injuries to his wing led to his passing. A taxidermist stepped in, and Peter stands sentinel today inside the Philadelphia Mint and reportedly has been used countless times by various coin artists as the inspiration behind a variety of eagle motifs on designs dating back to the 19th century.

Enter the Buffalo

Peter isn’t the only famous non-human numismatic model whose story is the stuff of legends. A bison by the name of Black Diamond has a story all his own. He is perhaps most famous for his appearance on the reverse of the Indian Head nickel, or “Buffalo” nickel. Struck from 1913 through 1938, the Buffalo nickel enjoys a beloved place in numismatics despite the fact that the coin’s common nickname is actually a misnomer, as the coin features an American bison – not a “buffalo.”

But differences in bovine taxonomy aside, the eponymous bison on the “Buffalo” nickel was literally and figuratively one of the biggest stars at a zoo in New York City. So, it’s little wonder that artist James Earle Fraser looked to Black Diamond in 1911 when he was designing what became the reverse of the Indian Head nickel. Fraser was inspired by his upbringing on the frontier and appreciation of Native American culture when designing the coin that he hoped could not be mistaken for being any other country’s coin.

In the January 27, 1913 edition of the New York Herald, Fraser recalled Black Diamond as a “typical and shaggy specimen” who was apparently “the most contrariest” of models. “I stood for hours watching and catching his forms and mood in plastic clay,” said Fraser. “Black Diamond was less conscious of the honor being conferred on him than of the annoyance which he suffered from insistent gazing upon him. He refused point blank to permit me to side views of him, and stubbornly showed his front face most of the time.”

At the ripe old age of 18 years, Fraser’s muse was older than most of his free-range Plains counterparts. But beyond these basic facts, the saga of Black Diamond and his place in numismatics is shrouded in mystique. Based on Fraser’s own words, scholars generally agree that Black Diamond must have been the inspiration for the Buffalo nickel design. But as with so many stories of numismatic lore, facts are muddled with conjecture and guesswork.

“Fraser stated the five-cent coin model was Black Diamond, but that the animal was at the New York Zoological Park,” confirmed researcher Roger Burdette, whose book Renaissance of American Coinage 1909-1915 (Seneca Mill Press, 2007) profiles the story behind the Buffalo nickel. “William T. Hornaday, founder and director of the New York Zoological Park, said that the animal was never at the New York zoo and was part of the display at the small Central Park Menagerie. Fraser likely confused the two zoos.”

Did Black Diamond Make Cameo Appearances On 1901 $10 Note & 30-Cent Stamp?

While the overwhelming consensus in the numismatic world is that Black Diamond modeled for the reverse of the Buffalo nickel, there is much more ambivalence on whether the shaggy New York bison is the starring bovine on the legendary Series 1901 $10 “Bison Note.” This note centrally features an American bison flanked by two portraits – those of iconic explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who from 1804 through 1806 journeyed 4,000 miles from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

According to some claims, the star of the 1901 $10 Bison Note is “Black Diamond,” but is this really true? According to Burdette, the beast on the note is not based on a single model but several. “The bison on the $10 bill is a composite of one from a group of stuffed specimens created by William T. Hornaday for the National Museum (now the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History) in 1889, and Pablo, a bison in the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C.” Further details on the matter reveal that in 1899 artist Charles R. Knight drew the bison visage seen on the $10 note using Pablo as the live model. However, around that time, Hornaday had removed a glass front on a display case housing the stuffed bison so a photograph could be taken for use by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

But do scholars really know for sure that Black Diamond was not the model on the Buffalo nickel? “Hornaday and Martin S. Garretson, Secretary of the American Bison Society are considered reliable sources,” noted Burdette. “Photos of the Smithsonian display are known and were published in Renaissance of American Coinage 1909-1915.”

And what about a popular United States 30-cent stamp released in 1923? The design, incorporating a bison, may remind some numismatic scholars of the Buffalo nickel, which in the mid 1920s was already in production and quite popular with the public. Surely, this has helped lead many to believe the depiction of the bison on the 30-cent stamp was based on Black Diamond’s likeness. But this simply isn’t the case. Chief postage stamp designer Clair Aubrey Houston chose the design from the 1901 $10 note as the inspiration for the motif on the 30-cent stamp.

Animal Tales: Separating Fact From Fiction

Fraser’s own accounts have essentially confirmed Black Diamond’s identity on the Buffalo nickel. Meanwhile, scholars have concluded, based on convincing evidence, that the $10 note vignette showcases not Black Diamond, but rather Pablo, and that this design directly spawned the motif seen on the 1923 30-cent stamp.

“Most of the ‘details’ are true legends – that is, they are not truthful but highly embellished imaginary concoctions,” stated Burdette. Such goes with the aforementioned case of Peter, the Mint Eagle – often cited in lore as the direct inspiration for various depictions of eagles on US coinage going back to the mid 19th century. “Evidently, this stuffed eagle sat around the Philadelphia Mint and might have been used for copying feather details from time-to-time. But since no realistic eagle appeared on U.S. coinage until 1907, its significance is very minor,” suggested Burdette. “As for the flying eagles on Augustus Saint-Gaudens double eagle coins and Hermon McNeil’s quarter, both were based on photographs as stated by the artists. Adolph Weinman’s eagles were romantic concepts whose feathers were based on a skein of goose wing plumage owned by James Fraser.”

Many people know what ultimately happened to Peter, the Mint Eagle; he still greets visitors at the Philadelphia Mint. But what was Black Diamond’s fate? Despite his fame, he met a most grisly end. By 1915, the aging beast had developed rheumatoid arthritis and became disabled. The menagerie offered the 22-year-old bison in an auction on June 28, 1915, but there were no bids, and when he was listed for sale at $500, there were no takers. Sadly, he met his fate at the slaughterhouse after a wild game meat company bought him for $300 and served him up as steaks at Delmonico’s in New York City. His head was mounted and his hide converted into a luxurious 13-foot automobile robe.

Black Diamond may be long gone, but his legacy lives on. “This hobby, like others, has its legends, heroes, rogues, icons and scallywags. That we incorporate other animals in our conjectures makes for greater fun and amusement,” posed Burdette. “Maybe one day, we’ll incorporate some plants. Imagine the fun we can have with a ‘Poison Ivy’ quarter!”

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to RQ Red Book Quarterly for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Source: CDN Publishing

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

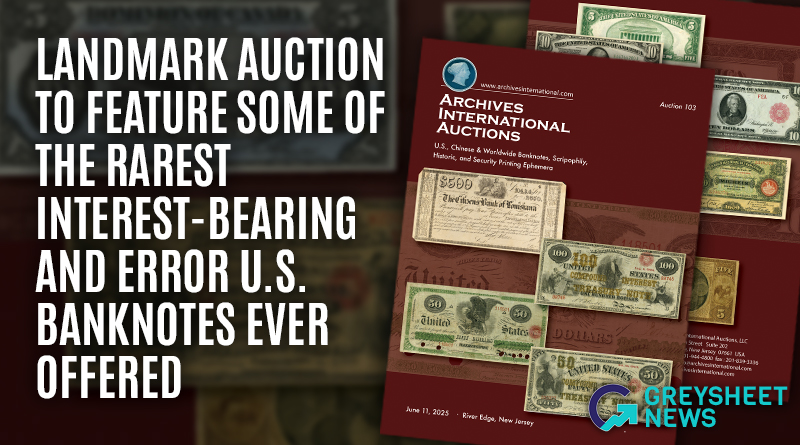

This sale presents an unprecedented opportunity for collectors to acquire museum-worthy examples from the nation's most pivotal monetary periods.

This relatively strong performance falls right between the prior two editions of this sale.

Greysheet Market Reports are the best way to stay current way on rare coin and paper money market info.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments