Collecting U.S. Twenty-Cent Pieces

This short-lived series from 1875-1878 remains extremely popular today with collectors, and includes on of the major rarities of the era.

One of the shortest lifespans for coin denominations in United States history was the Twenty Cent Piece, which was minted from 1875 to 1878. Only the $4.00 Gold Stella had a shorter minting period—just two years—1879 and 1880.

Why wasn’t that denomination successful here? Our neighbor to the north, Canada, had issued its Twenty Cent silver coin in 1858 and it was accepted and active in commerce. The Province of Newfoundland had an entire series of silver 20 cent coins circulating. As did Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, Russia, and Switzerland which all had silver coins denominated as a 20 in the local currency. So why was the American Twenty Cent coin such an abject failure? Let’s look at the history of how the coin came into being. John P. Jones was born in England in 1829, one of 13 children in his family. Two years later, the entire family emigrated to the United States. As Jones got older, he bought property in Nevada and did light manufacturing. By 1849, the gold rush was underway in California and Jones headed West. Although everyone who went there dreamt of instant riches, Jones applied himself to mining, but he also served as a County Sheriff, and in 1863, he became a Republican State Senator. His political career blossomed, and in 1867 he became the Republican candidate for Lieutenant Governor. A year later, Jones had moved from California to Nevada, and he became superintendent and then owner of the Crown Point Mine, which was part of the Comstock Lode. The success of the Comstock Lode was also beneficial to Jones financially.

Now with a background as a productive miner and as a politician, Jones was elected to the United States Senate representing Nevada. Jones was even more successful as a politician, serving five consecutive six-year terms from 1873 through 1903.

As someone who understood the value of silver, and owned mining interests, Jones championed the cause of alleviating the severe shortage of silver coins in the West. Compounding that problem was the fact that non-silver coins that were available like nickels were shunned and did not circulate. Westerners were reluctant to accept paper money or coins that were not struck from precious metals. There was a true coin shortage in the West and when coins were actually available, they were hoarded. Jones had a novel idea to solve that problem. Only one year after his election to the Senate, Jones proposed legislation to strike a new coin in a new denomination—a Twenty Cent piece.

The proposal was that this new coin would be made from western silver and minted at the Carson City facility. So, it drew a great deal of local assistance in Congress. In fact, mining interests all over the western United States threw their enthusiastic support to a new denomination of silver coin. As Jones gathered additional sponsors of his legislation in Congress his idea gained momentum. It passed the Senate, then the House, and also gained approval from United States Mint Director Henry Linderman. President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill into law and this new denomination was born.

Linderman had pattern coins struck and, unfortunately, decided on a design that displayed a Seated Liberty figure on the obverse and an eagle on the reverse. In order to help the general public from confusing the circulating Quarter Dollar with the new Twenty Cent piece, the latter would have a smooth edge rather than the standard reeded edges that Seated Liberty Dimes, Quarters, Half Dollars, and Silver Dollars all had. It was not quite enough to distinguish the new coin from its more valuable counterpart.

But another reason that was put forth for the need for a Twenty cent piece was the ability for that coin to be used in international trade. It would be equal to the French silver Franc coin. In fact, the Twenty Cent piece weighed in at 5 grams while the Quarter Dollar weighed in at 6.68 grams so the new coin would be closer in actual silver weight to the French coin.

Very few merchants in the 1870s, especially in the mid-West and Western states, wanted to accept the paper fractional currency that still circulated due to the shortage of silver coins. That was a particularly important reason for this emergence of this new coin, as the western mining interests continued to proclaim that fact.

Linderman had received sample pattern coins from James Pollock, the Superintendent of the Philadelphia Mint. It had a Seated Liberty obverse and a different reverse design, but it was rejected as being too similar to the existing quarter. Other patterns were also submitted for the Treasury Department’s approval.

On the final approved designs, some elements were missing that were on many other approved designs. “In God We Trust,” which been placed on coins since the 1864 Two Cent Piece, was missing as was the other popular motto “E Pluribus Unum.” It was deemed that the fields of the coin were too small to carry those messages. Unlike the Seated Liberty Quarter where the denomination was abbreviated to “QUAR. DOL.” on the reverse, the entire denomination of “TWENTY CENTS” was completely spelled out. The coin was now ready for striking.

The Seated Liberty Quarter, a coin that the public had been familiar with since 1838, was really the major culprit for resistance to the new Twenty Cent Piece. The Seated Liberty Quarter, which has been in circulation for nearly 40 years, was too similar to the new Twenty Cent piece. The Twenty Cent piece was a little smaller (22mm vs. 24.3mm) but that isn’t enough to recognize the difference between them unless you are comparing them side-by-side.

Additionally, both obverses had a version of Miss Liberty seated, holding a staff with Phrygian cap upon it and both had 13 stars on the obverse periphery with the date below. The reverse had different eagles and different denominations but for the general public, it was confusing. One would imagine that the Twenty Cent pieces were passed off as quarters on numerous occasions.

The final designs were approved in April of 1875 and production began at the Philadelphia Mint on May 19th. There 38,500 coins were struck for commerce and 1,200 Proof coins were struck for collectors. The new Carson City Mint went to work in June and struck 133,290 coins while the San Francisco Mint also began striking coins that month and minted 1,155,000 coins. That was, by far, the largest number of Twenty Cent Pieces struck in any subsequent year and the San Francisco Mint’s production during 1875 of these coins would be nearly ten times higher than any subsequent striking ever again.

In 1876, the Philadelphia Mint struck 14,750 coins for circulation and 1,150 Proofs for collectors. Many of the Philadelphia business strike coins were struck at the Mint Building that was at the Centennial Exposition, also being held in Philadelphia that year. As coins were placed into commerce, they very quickly became unpopular with the public. The similarity in size and design and the subsequent rash of complaints were the death knell for this unfortunate denomination. The Carson City Mint was the only branch mint in that year to strike any 1876-dated coins and they minted approximately 10,000 coins.

As complaints rolled into the Treasury Department and the mints, and demand for these coins was nearly non-existent, in 1877 Linderman ordered the melting of 12,359 of the Carson City coins—and that included some of the undistributed 1875-CC coins but nearly all of the 10,000 struck there in 1876. In fact, that action created a rarity for U.S. coinage. From that original 1876 minting of Carson City coins, less than 20 examples of those coins are known to exist today. It is speculated that these 20 or so coins may have been purchased by visitors to the Carson City Mint prior to Linderman’s missive to melt all undistributed coins. In August of 2022, Heritage Auctions sold an MS65 graded example of this classic American coin rarity for the record breaking sum of $870,000 including the buyer’s premium. That amount shattered the previous record of $540,000 from 2013.

The other virtually unattainable rarity in this series is a one-of-a-kind 1875-S Twenty Cent Piece that is considered a Branch Mint Proof or Special Striking. This coin was last sold by American Numismatic Rarities (now Stack’s Bowers) in 2004 for $104,000. To date, this is the only coin given such a designation by PCGS and the only coin endorsed by CAC to have cameo characteristics. Were any other similar coins struck? To date, none have surfaced.

In 1877 only 510 Proof coins were struck at the Philadelphia Mint and no uncirculated coins were struck at any mint. In 1878, the Philadelphia Mint struck 600 Proof coins but again no uncirculated coins were struck anywhere.

The complaints proved to be too much, and Congress abolished the denomination on May 2, 1878. All Twenty Cent coins on-hand at all of the mints, were to be recoined into other denominations and no further Twenty Cent pieces were to be struck ever again.

Jones’ experiment with this new denomination was a failure in the eyes of the public, but certainly not in the eyes of today’s collectors. But while this was a minor defeat for forces of silver and the western mining interests, they were richly rewarded with the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 requiring the government to purchase large quantities of silver every month, again from these western mining interests, and to have that silver coined into a new Silver Dollar coin. Hence the Morgan Silver Dollar was born, and the silver mines had their great victory.

For today’s collectors, only the extremely rare 1876-CC circulation coin and the rare 1875-S Branch Mint Proof are virtually unattainable. The other eight coins are available and form an important collection of short-lived western silver coinage.

Michael Garofalo has been a professional numismatist for more than 40 years. He was President of Liberty Numismatics and retired from APMEX where he was Vice President and Director of Numismatics. He is a Life Member of the American Numismatic Association and a member of the Numismatic Literary Guild.

Mike has recently published a book with CDN Publishing, titled “Secrets of the Rare Coin & Bullion Business from a Lifelong Trader.” Order a copy today at www.greysheet.com.

Coin images courtesy of Heritage Auctions, HA.com.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Michael Garofalo

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

When the United States took control of the Philippines, Congress enacted the Philippine Coinage Act of 1903 which established a new currency system based on the United States gold standard.

Weinman did not consider himself to be a coin designer or medalist, but instead referred to himself as a sculptural artist.

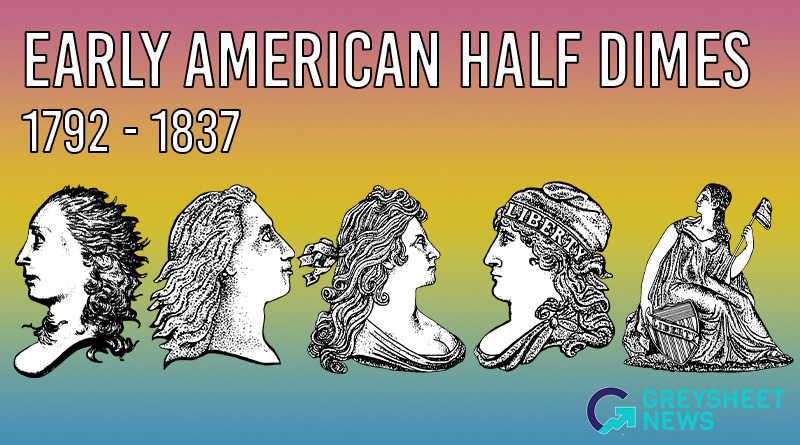

This earliest half dimes have been the subject of more than two centuries of rumors, innuendo, and conjecture.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments