Grant Stands Alone

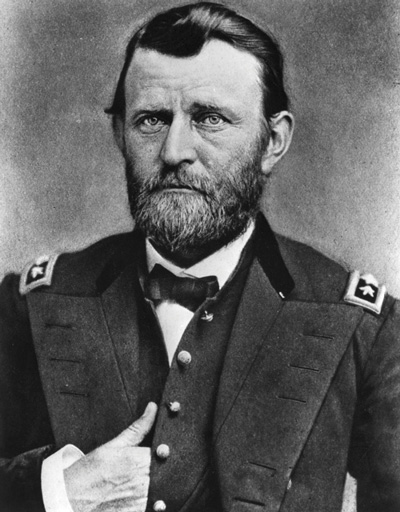

The President and General we know as Ulysses S. Grant was actually named Hiram Ulysses Grant at birth.

THE PRESIDENT AND GENERAL we know as Ulysses S. Grant was actually named Hiram Ulysses Grant at birth. He was born on April 27, 1822, in Point Pleasant, Ohio. His name was incorrectly entered into the records of the United States Military Academy at West Point when he accepted an appointment to the Academy. Grant refused to correct it and was forever known as U. S. Grant, a name which fittingly served him well as a General and later as President.

Grant fought in the War with Mexico and although in the quartermaster corps, he engaged in several important battles, but he felt the war with Mexico was “unjust.” However, as a young officer he did learn much about military planning and logistics, the role of leadership and the hierarchy of the military chain of command. After the war had ended, he took several more military assignments. But separated from his family and wife, he began to battle with alcohol, and it ultimately led to his resignation from the Army. Grant returned home but every business venture he began ended in failure and his career as a farmer was not much better. He was financially forced to accept a role in his father’s leather business in Galena, Ohio. But once the Civil War broke out, Grant knew what he must do.

As the Civil War divided the nation, Grant once again took up arms to defend his country. He likely felt some comfort in knowing that even though he would put his life on the line in battle, he was most successful in the role of soldier and leader.

Grant’s military career was hampered by Major General George McClellan and later by Major General John C Fremont. They frowned on his alcoholic exploits and considered him of weak character. But as they both took turns leading the Union forces, those military commanders themselves failed, so Grant was given more autonomy and started to build successes against the Confederates in battle after battle. Grant stood alone among Union generals for his success in battle. By early 1864, President Lincoln had ignored Grant’s personal past and focused on his successes in this war and named him Lieutenant General of the Union Armies. This title and rank had only previously been held by one man—Lieutenant General George Washington, during the Revolutionary War.

Grant’s military tactics and leadership saved the Union and he met with Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Appomattox, Virginia, to dictate the terms of the surrender of the Confederate Army. Grant could never understand why the South had taken up arms in order to defend slavery which he, personally, considered abhorrent.

After the assassination of Lincoln in 1865 and the disastrous presidency of southerner Andrew Johnson, Grant, the living hero of the Union, was elected President in 1868 and served two terms. When first elected he was only 46 years of age, the youngest man to that time to hold the office. He was also the first president to serve after Congress had officially outlawed slavery in the country.

Grant and his wife went on a world tour as an unofficial statesman for the US government and he served admirably. But Grant’s son had a business partnership in an investment firm with an unsavory character and the father tried to save the firm financially, placing himself into financial ruin once again. As poor health began to overtake him, Grant wrote his memoirs, not as a monument to himself, but to ensure that his wife would have sufficient funds on which to survive after his death. Grant was ill with cancer and died soon after the completion of his memoirs at age 63.

The Ulysses S. Grant Centenary Memorial Association was formed in 1922 to assist with the celebrations to be held in 1922. A bill asking for commemorative coinage to defray the costs of these celebrations was generated in the House and, after much negotiation, the bill did finally make it to the Senate. The bill that passed both the House and the Senate authorized up to 10,000 Gold Dollars and up to 250,000 Silver Half Dollars. President Harding signed it into law on February 2, 1922.

The Commission of Fine Arts was charged with finding a suitable sculptor for this coin and the decision was left to sculptor-member James Earle Fraser to select someone. Fraser judiciously selected his wife, Laura Gardin Fraser, to create the designs. Mrs. Fraser had previously designed the 1921 Alabama Centennial Commemorative Half Dollar, so she knew how the process worked and had great artistic talent. She worked rapidly and her designs for both the obverse and the reverse were quickly approved in March by her husband, the entire Commission of Fine Art, and the Secretary of the Treasury.

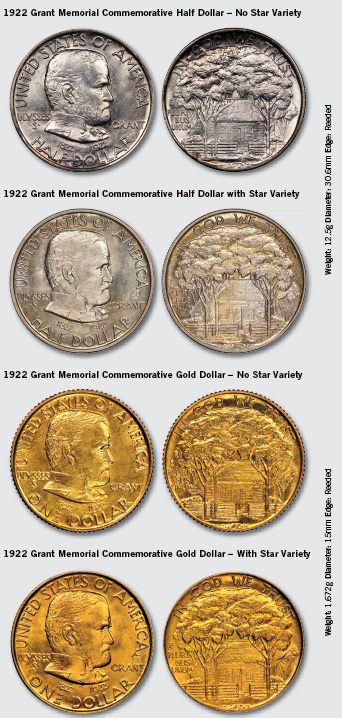

She used a Matthew Brady Civil War photograph of Grant for his portrait on the obverse of the coin. Grant’s bust faced to the right, and he was wearing his military uniform. His name is inscribed in the fields on the sides of his portrait with “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA” on the upper periphery, and the denomination “HALF DOLLAR” on the lower periphery. Below the bust are the dates “1822” and “1922” indicting his year of birth and the date the coin was struck.

The reverse depicts the farmhouse in which Grant was born, surrounded by a wooden fence and large trees. The reverse also bears the mottoes “IN GOD WE TRUST” and “E PLURIBUS UNUM” on the peripheries.

The Gold Dollar coin shares the exact same design, except for the denomination is different as is the metal and the size of the coin. In order to spur sales of the 10,000 Gold dollar coins, the Grant Centenary Memorial Association asked the US Mint to strike 5,000 of the gold coins with a symbol on them to make them distinct. The Mint chose a five-pointed star and struck 5,000 coins with the star.

However, without asking, the US Mint also struck 5,000 of the Silver Half Dollar coins with that same five-pointed star so the Memorial Association now had two coins—a Commemorative Half Dollar and a Gold Dollar. And they also had two varieties of each—with Star and without Star—to sell to raise funds for the celebrations, to preserve Grant’s childhood home, and to build a road in his honor connecting places that were significant in his life.

The coins with the star for each denomination were struck first and then all evidence of the star was removed from the dies before striking the rest of the coins. Reportedly, the Association also asked the Mint if they would strike some of the coins in Proof condition, but the Mint declined to do so, stating that they had not struck Proof commemorative coins for a number of years and had no plans to do that again. Though some dealers and collectors believe that Proof Grants do exist.

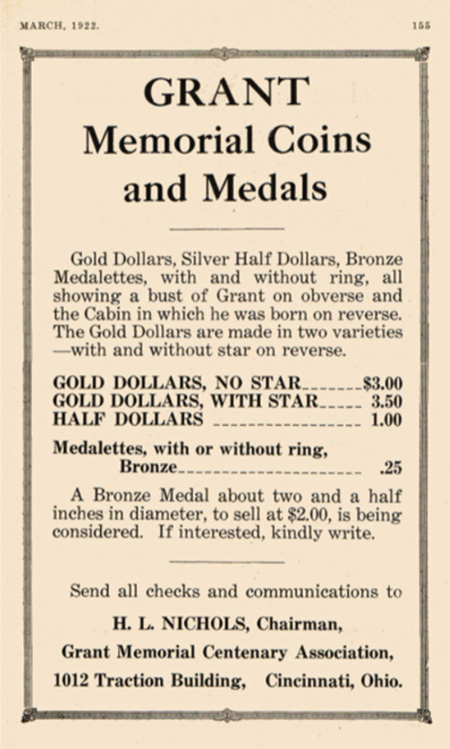

In the March 1922 issue of The Numismatist, the monthly publication of the American Numismatic Association (ANA), the first announcements about the Grant Commemorative coins were published. The advertisement placed by the Grant Memorial Centenary Association offered Gold Dollars with Star, Gold Dollars without Star, and Half Dollars (without Star), as they had no idea the Mint would strike the Commemorative Half Dollar in both varieties.

The April 1922 issue of The Numismatist relates the first story of these coins and notes an interesting fact:

“The Grant coins differ from other commemorative coins heretofore issued in that there is no inscription on them telling of their nature or object—no reference of a Grant Memorial—the designs alone telling the story.

In design and execution, they are the equal of any of our recent commemorative issues, all of which have proved exceedingly popular with collectors.”

But while the coin collecting community raved about the beautiful designs, the designer was concerned about her work. Laura Gardin Fraser chose to sign her coins with a simple “G” initial, rather than the “LGF” that she used on the 1921 Alabama commemorative Half Dollar, just a year earlier. The reason that she changed it was that she worried that her husband, the artist on the Commission of Fine Arts would be accused of nepotism by offering his wife the chance to design the Grant commemorative coins. She felt that if she signed it with only a “G” (for Gardin, her maiden name) it would be less obvious as to whom the designer actually was.

In that same April 1922 issue of The Numismatist the Memorial Association offered the coins for sale to the ANA members and to the general public. The ad included the warning that the sales would close by January 1, 1923.

The coins were originally priced as follows:

• Gold Dollars, with Star - $3.50

• Gold Dollars, without Star - $3.00

• Silver Half Dollars, with Star - $1.50

• Silver Half Dollars, without Star - $1.00

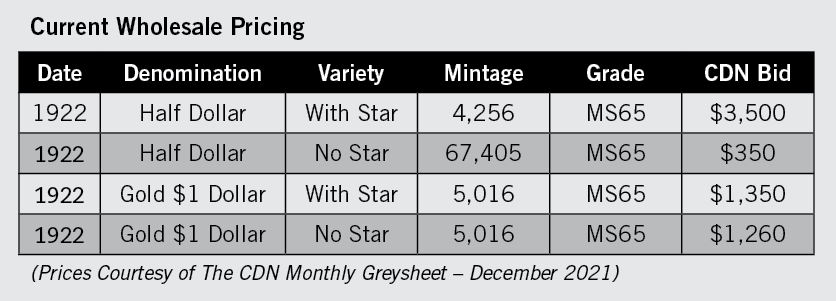

By August of 1922, sales were not quite what the Association had expected. A prominent dealer was offering Five Grant Memorial Silver Half Dollars (without Star), a Grant Memorial Gold Dollar with Star and a Grant Memorial Gold Dollar without Star for only $10.00. This price was well under the US Mint’s initial March offering of $11.50.

By the September issue of The Numismatist, even the Memorial Association realized that sales would be slower than expected and they reduced the price of the Silver Half Dollar without a Star to only $.75 per coin.

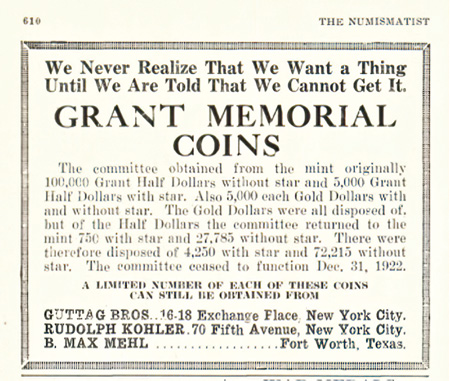

By December of 1923, the Association had disbanded, and the unsold coins were returned to the US Mint for melting. Three inventive dealers of the day—B. Max Mehl, the Guttag Brothers and Rudolph Kohler teamed up in advertising in The Numismatist to relate that all of the coins from the Mint were gone, but you could buy some of these rare and valuable items from each of them.

The advertising for the Grant Memorial Commemorative Coins, in the March 1922 Numismatist, page 155

Advertisement in the December 1923 issue of The Numismatist

The Grant Memorial Commemorative Half Dollars and Gold Dollars, with and

without Stars, were the only commemorative coins struck in 1922. Other

future commemorative coin legislation was discussed during that year—the

upcoming 1923 Monroe Doctrine Centennial, the 1924 Huguenot-Walloon

Tercentenary. There was even a discussion about striking a 1922 Rutherford

B. Hayes commemorative coin for the October Centennial of his birth, but it

never passed through the committee to become legislation.

Why were there so few commemorative coins struck in 1922? The reason will also explain why the Lincoln Cent was only struck in Denver that year and why there are no nickels, dimes, quarters, or half dollars dated 1922.

All three of the United States Mints were too busy dealing with the effects of the Pittman Act in order to create new dies and strike many 1922-dated coins. The Pittman Act removed over 270 million Morgan Silver Dollars from the Treasury’s vaults and melted them and converted them into bullion. The silver bullion was then sold to Great Britain to help them with the bullion crisis they were facing and to restore faith in Great Britain’s paper currency.

But the Act also required the purchase of a like number of ounces of silver

from American silver mines and that silver was to be used to create more

new silver dollars. That explains why all three US mints were busy striking

over 98 million 1921-dated Silver Dollars and over 84 million 1922-dated

Peace Silver Dollars. Even gold coin striking was greatly curtailed as only

1922 and 1922-S mint $20.00 Gold Double Eagles were struck that year.

Ulysses S. Grant stood alone among all of the Union Civil War generals. He alone had the confidence and full support of President Lincoln and Grant’s successes guaranteed it. After Lincoln’s assassination and the disgrace of Andrew Johnson’s impeachment and near acquittal, Ulysses S. Grant again stood alone on the national stage to become President and lead the Reconstruction effort. It is almost fitting that in 1922 Grant’s Memorial Commemorative coinage should also stand alone in the annals of numismatic history.

Michael Garofalo has been a professional numismatist for more than 40 years. He was President of Liberty Numismatics and retired from APMEX where he was Vice President and Director of Numismatics. He is a Life Member of the American Numismatic Association and a member of the Numismatic Literary Guild.

Mike has recently published a book with CDN Publishing, titled "Secrets of the Rare Coin & Bullion Business from a Lifelong Trader." Order a copy today at www.greysheet.com.

Images courtesy of NGC, www.ngccoin.com & ANA, www.money.org

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Michael Garofalo

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

When the United States took control of the Philippines, Congress enacted the Philippine Coinage Act of 1903 which established a new currency system based on the United States gold standard.

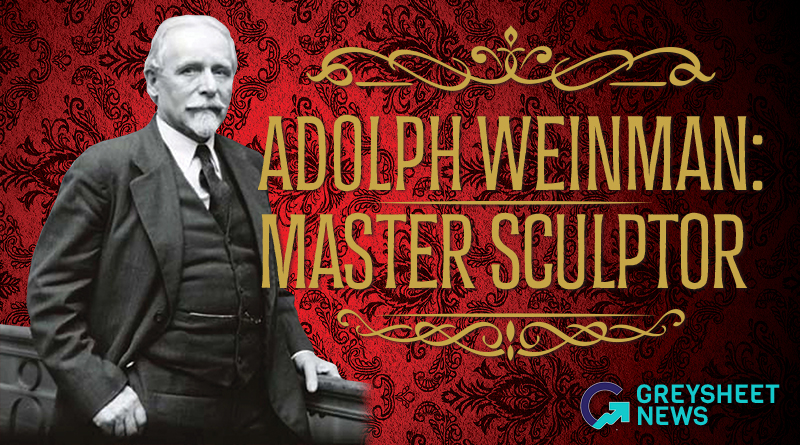

Weinman did not consider himself to be a coin designer or medalist, but instead referred to himself as a sculptural artist.

This earliest half dimes have been the subject of more than two centuries of rumors, innuendo, and conjecture.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments