POST-WAYFAIR TAXES: WHERE THEY CAME FROM & WHERE THEY ARE GOING

The state tax changes resulting from the Supreme Court’s Wayfair decision will have profound affects on small businesses, including rare coin dealers. Patrick Ian Perez explains explains not only what happened, but also how and why it happened.

by Jimmy Hayes, ICTA Executive Director

If you lose, you will continue to lose until you know why you lost. The current State taxation initiatives resulting from the Supreme Court’s Wayfair decision will not be successfully responded to with a federal legislative replacement until small business understands and reacts to not only what happened, but also how it happened and why it happened.

BIRTH OF THE SALES TAX NATION

The phrase “No taxation without representation” became a rallying cry supporting an American Revolution. One cannot help but wonder what the 1770s colonists would think of today’s “Taxation with Representation” being imposed by state after state.

In 1789, when the Constitution creating a United States was adopted, few of these newly minted Americans had ever heard of a “sales” tax. Those who drafted the Constitution were very mindful of the “tariffs and fees” related to trade and made it clear that no state should take an action to unduly burden or inhibit the flow of commerce among the newly created states.

The very first Article of the Constitution addresses Legislative powers over Commerce and illustrates the desire that the legislative branch of the federal government would exercise the exclusive power to maintain the free flow of goods between states.

It was not until the Great Depression in the 1930’s did Mississippi and Kentucky institute what were described as “temporary” taxes imposed upon retailers as a necessary means to combat the devastation to the state budgets. Quickly learning of this inventive source of revenue, an additional eleven states instituted sales taxes by 1933.

Most of the newly created “sales taxes” were promoted as the means of generating revenue for specific public needs such as bridges, water treatment facilities, and public buildings. The sales tax often played the role today occupied by bond issues.

By 1940, thirty states had enacted laws authorizing sale tax collections, often without dedicating the revenues. By 1947, sales tax receipts were the largest source of revenue for states. But the peak collections in the 1950’s began to dwindle. The legislative response at the local and state level was to raise sales tax rates, or in many instances institute county and city sales taxes in addition to the existing state sales taxes.

Aided by the technology generated during World War 2, the construction of roads and bridges became part of an ambitious interstate highway system, a more advanced rail system, and a booming aviation industry. The landscape where and how commerce occurred were being dramatically altered.

A new subject for “sales” was also ballooning, the interstate delivery of “services” uncovered and beyond the reach of sales tax laws was adding to the rapidly shrinking “sales tax” revenues. By 1970, the state budgets averaged a little over 30% of revenues from sales tax collections, about half of the percentage twenty years earlier. The sales tax “piggy bank” was getting smaller and smaller as states began to realize their limitations on taxing “interstate sales.”

STATE FRUSTRATIONS WITH “TAX FREE” INTERSTATE SALES

The States recognized the need to establish a “connection” between the out of state seller and the state resident buyer. The connection, called nexus, was not clearly defined in law, but its establishment was the only means the state taxing authorities could avoid the two major obstacles to collections of sales taxes:

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits any state action that would “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without the due process of law. In order to tax the sale made from outside the state to a state resident, the seller must have a connection described as a “nexus” linking the out of state seller to the state seeking to impose a sales tax.

The Commerce Clause of Article I of the Constitution had consistently been interpreted by the Court to allow only Congress to “regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States” which the Court interpreted to prohibit a State from enacting legislation imposing an undue burden on commerce among the states.

Some states determined that a “use tax,” instead of a “sales tax,” could be imposed upon the state resident who purchased something from a seller either within or outside the state. The “use” of the purchased item, no matter where obtained, would obligate the state resident to pay for such “use.”

The “use tax” concept while legally workable had two major defects. First, there was often a limitation to the application of the law. Purchases having a fixed useful life seemed most suitable for “use” by the purchaser, opening the door for numerous exclusions of many items. The second defect was the inability to enforce the tax upon buyers from out of state sellers. Voluntary disclosure found few volunteers and harsh enforcement found few supporters among those holding an elective office.

A few States undertook Court initiatives in order to test the waters for state laws reaching outside state boundaries. Most attempts failed completely but a most notable Supreme Court case slightly advanced state “nexus” arguments. A 1960 Supreme Court decision held that a Georgia corporation with ten “independent contractors” working on sales commissions and physically present in the State of Florida were determined to be working on behalf of the out of state company. Therefore, such contractors were subject to the same consideration as employees and thus could serve to establish nexus between the Georgia company and the State of Florida.

However, States suffered a major setback in 1992 when the Supreme Court ruled that the Quill Corporation, a company with a significant direct mail sales mechanism in the State of North Dakota, including a software program used by North Dakota residents for placing direct orders was not “physically present” in North Dakota. The lack of “physical presence” prevented the North Dakota Department of Revenue from requiring the Delaware corporation to remit sales taxes on purchases by North Dakota residents.

For decades the Court’s ruling stood, as technology continued to accelerate to the point where volumes of sales dwarfed everyone’s expectations. “Brick and Mortar” local businesses and shopping center tenants became convinced that the interstate tax free sales and particularly the “internet tax free sales” were the cause of every local business decline.

Although the internet itself no doubt drove declines, the “interstate sales tax free status” was only one of many factors causing local businesses to suffer losses to internet sellers. The savings brought by the absence of sales taxes were often offset by shipping costs and handling fees. The major forces driving interstate sales were a combination of convenience of delivery, and lower prices from sellers who did not have large “brick and mortar” rent or mortgage expenses and employee benefit costs. In many instances, the seller’s cost was significantly lower, creating the most significant sales advantage.

Just as decades before large grocery chains outpriced small grocery stores, the interstate sellers could undercut the pricing in the “brick and mortar” stores in many categories of sales.

Through an evolution of State laws seizing upon the large national retailers “substantial nexus” with the State because of the “physical presence” of distribution centers, contractual sales arrangements, licensing agreements or various other contact points, more and more large retailers were entering into “voluntary” sales tax payment agreements with States. At least one large internet retailer (Amazon) created for itself a new business “identifying, collecting and remitting sales taxes” through service contracts with large retailers such as Walmart.

The large retailers who had not been able to avoid “physical presence” or shield their internet associated operations from taxation often supported the local small business efforts for ”sales tax fairness.” However, the large national retailers’ motivations were not quite the same as small business. The large retailers viewed the issues from an additional perspective since their competition was made up of both intrastate and interstate smaller sellers. Like the “little grocery stores” who could not match the national chains, large national retailers used vast resources to remove competition. A so-called “tax fairness” in the eyes of a local seller was anything but “tax fairness” imposing upon small business remote sellers the costly burdens of compliance. Such an outcome was a very acceptable consequence for those large national sellers who were already paying the sales taxes in many States.

While little could be accomplished by any one state legislature, sales tax supporters concentrated their approach to the state legislative level to embrace an alliance of states collecting sales taxes. One such effort was the support of a State “compact” concept known as the Streamlined Sales Tax Project begun in March 2000.

The resulting “Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement” attempted to entice states and localities to join together in reciprocal arrangements for imposition and collection of sales and use taxes. As could be expected, the task was not easily accomplished. As a result of several compromises upon what commitments a state was required to make and meet, different levels of membership were allowed in order to prevent stalemates over differing approaches. Nevertheless, the SSTP was a step toward expansion of State authority.

However, it became clear that the Streamlined Sales Tax Agreement alone would not accomplish the desired goals as long as the Supreme Court’s imposition of the “physical presence” barrier remained.

CONGRESSIONAL PUSH FOR STATE SALES TAX AUTHORITY

Since Federal Courts were still following the 1992 Quill decision’s “physical presence” the supporters of expanding the States’ ability to require collection and remittance of sales taxes turned to the Congress, vested with the Constitutional authority over interstate commerce. In fact, the Supreme Court had on several occasions urged the Congress to legislate the criteria for determining the “nexus” necessary to establish the state authority to impose sales tax obligations on an out of state seller.

The large retailers gathered support from groups comprised of Governors, State Representatives, “brick and mortar retailer stores” trade associations and pushed legislation known as The Marketplace Fairness Act, the purpose of which was described as an effort “To restore States’ sovereign rights to enforce State and local sales and use tax laws, and for other purposes.”

It is instructive to note that the legislation attempted to use a “carrot and stick” approach. A State was required to join the Streamline Sales and Use Tax Agreement in order to require out of state sellers to collect and remit takes to the buyer’s state. The Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement was required to include specific minimum simplification and other requirements outlined in the legislation.

States choosing not to enter into the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement could alternatively agree to a set of minimum requirements contained elsewhere in the legislation. Those who chose neither option could not enforce sales tax collections and remittance from out of state sellers.

The proposed legislation contained a small seller exception consisting of a $1,000,000 nationwide receipts threshold. In an attempt to avoid tax expansions, the legislation prohibited franchise, income, occupation and any other type of taxes other than sales and use taxes. Specific exemptions were provided by excluding any changes to the Mobile Telecommunications Act provisions.

The legislation was quickly and successfully passed by over 90 votes in the Senate but stalled in the House Judiciary Committee when those who actually read and carefully examined the Senate Bill began to realize an almost endless list of “unintended consequences” potentially having a devastating on interstate commerce.

House Judiciary Committee Hearings exposed serious defects and flaws in the Senate language. Several alternative bills were drafted in an effort to address such deficiencies but none gained enough support for passage. Large retailers actively opposed most such measures. Without reading minds, one could guess that things like keeping the site of the sale with the out of state seller who would collect whatever sales taxes would be paid as if the sale was intrastate did nothing to further the national retailers’ agenda. Similarly, multiple efforts to enlarge thresholds and clarify sales tax restrictions and add to specific prohibitions were doomed.

Wayfair company logo

SOUTH DAKOTA V. WAYFAIR INC.

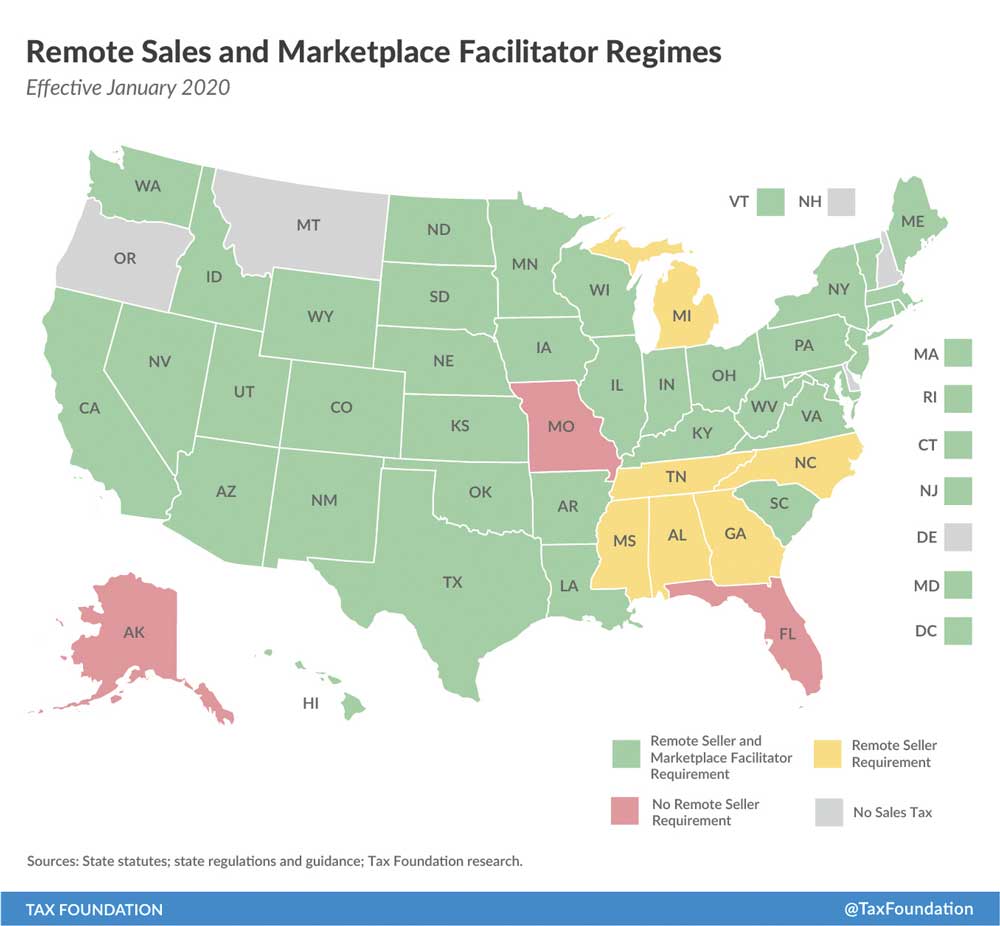

The Supreme Court Decision in Wayfair is not nearly as important for what it says as it is what it does not say. The five to four opinion written by Justice Kennedy can be summed up in a few words. States no longer need to prove an actual “physical presence” of an out of state seller in order to impose sales tax collection and remittance obligations. The Quill decision’s “physical presence” requisite was overturned by the one vote majority.

What the Court did not say was “The State can tax anyone anywhere who does anything.” However, that appears to be what was heard by most State legislators in search of money to spend. Post-Wayfair State tax initiatives repeat and adopt either those things prohibited in the proposed Marketplace Fairness Act or the “unintended consequences” listed by the witnesses in the House Judiciary Committee hearings on the Marketplace Fairness Act. In less than eighteen months, one or more States have imposed, among other things:

Taxes on goods and services sold by any means (internet or otherwise) to residents by sellers across State lines even if the out of state seller made no other sale within the state;

Filing requirements on out of State sellers in order to qualify to do business in the State, even before any sale has been made;

Franchise taxes on corporations making sales treated as “doing business” in the state;

State income taxes on profits from the remote sale in addition to the sales taxes;

Taxes on goods or services sold by auction houses or other “facilitators;”

The list goes on and on, without an end in sight. Until Federal legislation is passed to supply what “Wayfair does not say,” out of state sellers will continue to be buried beneath often impossible burdens.

ICTA’S PATHWAY TO SUCCESS

What not to do:

Do not attempt to move through Congress a complicated rerun of the Marketplace Fairness Act.

What to do that has a much greater chance of success:

Use existing laws as vehicles for making significant changes a few at a time, as for example:

Amend the Interstate Income Tax Act (P.L. 86-272, 15 USC 381) by clarifying “tangible personal property” definitions and add “services” in addition to “goods.” Furthermore, specifically limit or exclude “tax audits” on out of state sales of goods and services.

Incorporate the language identifying Exemptions and Exclusions written into the Marketplace Fairness Act into new limited legislation. This approach has the advantage in the Senate of having been previously supported by the votes of a large majority of current Senators.

Attempt to place language into legislation that would exempt from interstate sales taxes any items or goods allowed to be included in an IRA investment or which is subject to the Capital Gains Tax “as an investment” upon its disposition.

The approaches listed are not the only approaches, but represent the concept of using an existing law in order to further its original purpose in the light of “unintended consequences” of the Wayfair decision. Each instance also recognizes that any effort required the building of alliances far greater in number and economic impact than any one business. Some of the former “supporters” have now become targets of unintended consequences. The opportunity for success requires the resources to put together coalitions in order to achieve that success.

PATHWAY TO FAILURE

The partial list above is not borrowed or copied from anyone. ICTA’s experience and knowledge of these issues is what makes ICTA’s value much greater than its size and membership would merit. However, ICTA does not operate on an unbalanced budget, and right now resources are committed to efforts to stop bullion and numismatic sales tax exemption repeals in six different states.

Please join us (www.icta.com) or help us to help your small business whose voice was left out.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Patrick Ian Perez

Patrick Ian Perez began as a full time numismatist in June of 2008. For six years he owned and operated a retail brick and mortar coin shop in southern California. He joined the Coin Dealer Newsletter in August of 2014 and was promoted to Editor in June 2015. In the ensuing years with CDN, he became Vice President of Content & Development, managing the monthly periodical publications and data and pricing projects. With the acquisition of Whitman Brands, Patrick now serves as Chief Publishing Officer, helping our great team to produce hobby-leading resources.

In addition to United States coins, his numismatic interests include world paper money, world coins with an emphasis on Mexico and Germany, and numismatic literature. Patrick has been also published in the Journal of the International Bank Note Society (IBNS).

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

One of the best ways to gauge the market is to measure how aggressive dealers have been in their wholesale buying.

July is always one of the quieter months on the numismatic calendar, as vacations and rest and relaxation take a little priority.

Dramatic swings both ways, but mostly in the upward direction, have commanded the headlines.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments