The Meaning of An Irrevocable Bidder

On June 8, while Sotheby’s was auctioning the Fenton-Weitzman 1933 double eagle, an irrevocable bidder turned out to be the winning bidder. In many cases at Sotheby’s, though, the irrevocable bidder for a particular lot is not the winning bidder.

On June 8, while Sotheby’s was auctioning the Fenton-Weitzman 1933 double eagle, an irrevocable bidder turned out to be the winning bidder. In many cases at Sotheby’s, though, the irrevocable bidder for a particular lot is not the winning bidder.

By being the irrevocable bidder, the buyer was able to pay $18,872,250, rather than $19,509,750. If the underbidder had been the successful bidder, he would have had to pay $19,222,500, more than the winning bidder paid with a higher hammer price. How could this be?

In the online catalogue, there were symbols above the lot description for this 1933 double eagle indicating that it was both “Guaranteed Property” and subject to “Irrevocable Bids.” For a lot to be guaranteed property, Sotheby’s or a third party or some combination of Sotheby’s and a third party agree in advance of the auction to bid the consignor’s reserve or an amount above the consignor’s reserve. The term “Guaranteed Property” means that the indicated lot will definitely sell in the respective auction.

The concept of an irrevocable bidder is different from the concept of a guarantee that the lot will sell. Yes, the irrevocable bid of an irrevocable bidder may also be the guarantee thus the same person is often a guarantor and an irrevocable bidder. The guarantor and the irrevocable bidder, however, may be different people or different firms.

If the guarantor is a third party, he is paid a fixed fee to bid a certain amount, presumably at or modestly higher than the reserve. His compensation for being a guarantor is thus fixed regardless of the outcome of the auction.

If the symbol for irrevocable bids above the lot description for the 1933 double eagle is clicked, a popup box appears with a definition that is far more narrow than the definition of an irrevocable bidder in the Conditions of Sale section of the same online catalogue. I am citing the broader definition here, which I find to be ambiguous. The following part is especially relevant to the sale of the Fenton-Weitzman 1933 double eagle.

“The irrevocable bidder, who may bid in excess of the irrevocable bid, may be compensated for providing the irrevocable bid by receiving a contingent fee, a fixed fee or both. … If the irrevocable bidder is the successful bidder, any contingent fee, fixed fee or both (as applicable) for providing the irrevocable bid may be netted against the irrevocable bidder’s obligation to pay the full purchase price for the lot and the purchase price reported for the lot shall be net of any such fees.”

As Sotheby’s charges different buyer’s fees for different price ranges, the compensation for an irrevocable bidder may possibly amount to different percentages of different price ranges, components of the winning hammer bid. My interpretation is that the compensation of an irrevocable bidder is likely to be at least partly based upon the size of the winning hammer bid. A guarantor, in contrast, receives the same fixed fee regardless of the size of the winning hammer bid.

“In addition, from time to time, an irrevocable bidder may have knowledge of the amount of a guarantee,” it is said in the definition in the Conditions of Sale. This sentence indicates that the guarantor and the irrevocable bidder may be two different people in some cases. It follows logically that the irrevocable bid may be significantly above the guaranteed selling price established by the guarantor. Presumably, an auction firm may first contract with a guarantor for a lot or the auction firm itself may be the guarantor, and then later contract with a collector to be the irrevocable bidder.

If the irrevocable bidder is a dealer or a speculator, then he is incurring risk. No one can come close to perfectly estimating market levels for very rare or otherwise especially distinctive items.

If the irrevocable bidder is a collector who really desires the item, he has a tremendous advantage over the other bidders, especially if his pre-auction irrevocable bid is much less than he is willing to pay to obtain the item for his own collection. In the case of the Fenton-Weitzman 1933 double eagle, it seems likely that the irrevocable bidder is a collector who strongly desired this coin and was very much willing to pay a retail price for it.

Copyright ©2021 Greg Reynolds

Insightful10@gmail.com

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Source: Greg Reynolds

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

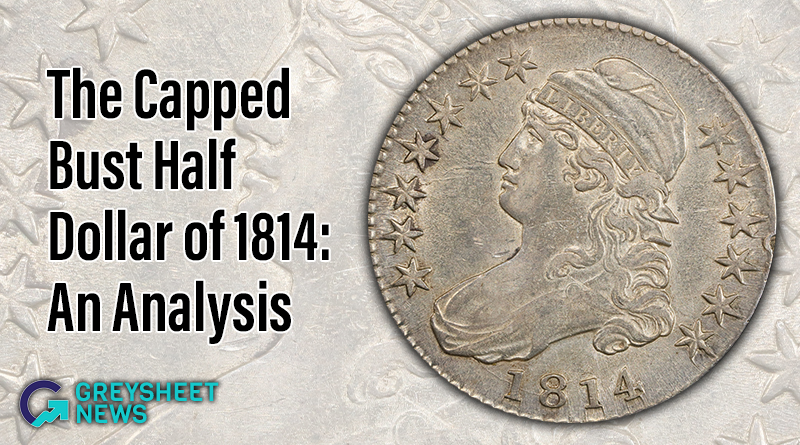

In this article Greg Reynolds analyzes the 1814 Capped Bust Half Dollar.

The Lusk set of Draped Bust quarters brought strong results.

The 1889-CC is the second scarcest business strike in the series.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments