Why Are Partrick Collection Brasher Doubloons Worth So Much?

An initial reporting of in-depth analysis of the the Panoramic Partrick Collection.

On January 21, a special Partrick Collection Platinum Night session was conducted by Heritage at this firm’s new headquarters near the Dallas Fort Worth Airport (DFW). There was such a wide variety of rare and exceptionally interesting items in this Partrick Platinum Night event that it is not practical to fairly cover many of them in one discussion. This report is about the Brasher Doubloons. Future analyses will cover additional items from the Donald Partrick Collection.

Generally, the term “Brasher Doubloon” is used to refer to ‘New York Style’ gold pieces produced by Ephraim Brasher, a famous silversmith and goldsmith in New York City during the 1780s. These are slightly lighter, on average, than uncirculated Spanish Doubloons of the 18th century, large gold coins of the Spanish Empire. Circumstantial evidence suggests that surviving ‘Lima Style’ and ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons are about the same weight as typical, worn Spanish Doubloons that circulated in New York and elsewhere in the United States during the late 18th century.

In 1786, Brasher’s firm designed and minted ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons, of which just two are known, including the Partrick Collection coin. There are seven surviving ‘New York Style’ pieces. There also exists one ‘New York Style’ Brasher Half-Doubloon, which is in the Smithsonian.

1786 Lima Style Brasher Doubloon graded NGC MS61 CAC from the Patrick Collection (Images courtesy of NGC Photo Vision)

While the 1787 ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons are of original designs with words and artistic concepts that were associated with the State of New York or the United States as a nation, 1786 ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons resemble Spanish Doubloons that were minted in Lima during the 1740s. Lima is now the capital of the nation of Peru. Spanish Doubloons circulated widely throughout South America, Central America, the Caribbean and North America.

The 1786 ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons were true coins. It would not make sense for patterns, tokens or experimental pieces made in New York to be so similar to doubloons of the Spanish Empire. Evidently, all known Brasher Doubloons were stamped by Brasher himself with his hallmark, which was impressed upon coins that Brasher determined were of appropriate weight and fineness for circulation in and near New York. The resemblance of these to true Spanish Doubloons is such that these must have been produced by Brasher to circulate as coins. Why else would they have been made?

In a document published by the Bank of New York in 1784, it was stated that this bank would pay $15 for any Spanish Doubloon of ‘17 pennyweights’ (408 grains). Standard Krause references indicate that the specification in the Spanish Empire was for a Spanish Doubloon in the 18th century to weigh 27.0674 grams, which equals 417.71 grains or 17.405 pennyweights. My belief is that officials at the Bank of New York were either rounding down, or, more likely, were figuring that many of the Spanish Doubloons encountered in New York in the 1780s were not nearly uncirculated and tended to weigh around 408 grains (“17 Pennyweights”), give or take a few grains. The weights of both known ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons are each very close to the 17 pennyweights (408 grains) parameter listed by the Bank of New York in 1784. The weights of the seven surviving ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons are each close to 408 grains, and each weighs less than the 417.71 grains that an uncirculated Spanish Doubloon was specified to weigh according to standard references by Krause Publications, now part of Penguin Random House.

Crucially, before the 19th century, fair imitations of foreign coins that circulated widely in a society were often considered by merchants to be legitimate coins, not counterfeits. Besides, as Brasher featured his last name on each ‘Lima Style’ and ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloon, it was obvious that he was announcing that his firm made them.

‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons were similar enough to true Spanish Doubloons of the 1740s that they would fit in with a group of them. Brasher probably concluded, however, that minting ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons was more of a hassle than it was worth. Much work was involved in making them and ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons were probably accepted by pertinent businessmen only to a limited extent.

If there was enthusiasm for ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons, these would have been mentioned in accounts, letters and/or newspapers during the 1780s. The response to them was probably not as positive as Brasher hoped. Ephraim Brasher was a very well known silversmith.

During the 18th century, silversmiths and goldsmiths often adjusted the amount of precious metal in circulated gold coins from foreign societies so that each piece met the standards of the society where it was circulating or the expectations of international traders. During the 1780s, Brasher was one of several silversmiths in the United States who regulated gold coins and attested to their proper weight by stamping them with an identifying hallmark. To some extent, a silversmith was guaranteeing the weight and fineness of each gold coin that he regulated and stamped. Regulating often involved adding gold to coins to meet local standards and/or because gold coins arriving from foreign societies were often heavily worn, clipped or damaged.

In this same Partrick session, there were auctioned Portuguese, Brazilian and British coins that were stamped by Brasher. For example, an NGC graded XF45, 1766-R 6400 Reis gold coin of Brazil that featured Brasher’s hallmark brought $126,000, a strong price.

A 1766-R 6400 Reis gold coin of Brazil featuring Brasher’s hallmark (Images courtesy of Heritage and NGC)

The Newcomer-Garrett-Partrick, ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloon was NGC graded as MS61 and approved by CAC. As do most all MS61 grade 18th century gold coins, it has very apparent technical imperfections. Nonetheless, it is of higher quality than I expected it to be, clearly superior in quality to more than a few U.S. gold coins from the 1790s that have been graded MS61 by NGC or PCGS.

As ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons are rarely seen publicly and both survive in the shadows of ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons, I was figuring that a retail value for this coin would be under $2 million. The $2.1 million result was strong, though not nearly as strong as the result for the Garrett-Partrick ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloon. This coin is neat and fascinating. ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloons are probably the first gold coins minted in the United States.

I feel fortunate to have examined the other known ‘Lima Style’ Brasher Doubloon as well. It was NGC graded XF40, part of “The Gold Rush Collection,” and auctioned by Heritage for $690,000 on January 12, 2005. It had appealing color, though some serious scratches were distracting.

The $9.36 million result for the finest known ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloon was very strong. Before the auction, I though much about it and consulted market players. I figured that a dealer buy-price would be in the $5 to $6 million range and a retail level would be in the $6.5 to $8 million range.

Because of the fame, quality, distinctiveness, and role in the history of coin collecting, of this Brasher Doubloon, it is especially difficult to estimate its value. The $9.36 million price paid is sensible. This certainly was a much better value than the Simpson Collection Proof 1804 eagle, which was auctioned for $5.28 million the evening before the Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon was auctioned.

The Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon with 'EB' Mark stamped on the wing (Images courtesy of Heritage and NGC)

This same Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon set a then astonishing auction record in 1907 in the sale of the Matthew Stickney Collection by the firm of Henry Chapman. The $6200 auction result in June 1907 was probably more than double the auction record before 1907 for any American numismatic item. Ever since then, this particular Brasher Doubloon has been a towering presence in the realm of coin collecting.

In the same sale from the same Matthew Stickney Collection, there were two 1795 eagles, one brought $27 and the other went for $20. Although catalogued as “Extremely Fine,” the 1795 eagle that then realized $27 would be likely to grade somewhere between AU-55 and MS-63 in accordance with today’s standards if it could be magically transported through time in its same state of preservation.

The Stickney Collection is one of the greatest of all time. It is likely that each of Stickney’s 1795 eagles would wholesale now for more than 2000 times their respective auction prices realized in 1907, perhaps even more than 4000 times as much.

In an auction by the Chapman brothers in May 1906, one of three known 1822 half eagles realized $2165. Hypothetically, if this same 1822 half eagle had been in the Partrick Collection, it would have realized millions of dollars, possibly 3000 times as much as it realized in 1906.

An immediate point is that the current $9.36 million price for the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon is in line with most price ratios regarding famous rarities in the Stickney sale of 1907 and in other major auctions of that time period. Moreover, many coins in that sale in 1907 are worth more than 2000 times as much in 2021. If the $6200 result for this Brasher Doubloon in 1907 is multiplied by 2000, the product is $12.4 million. Of course, the preferences and demands of coin collectors change over time. Nonetheless, as 18th century U.S. gold coins and famous rarities from the early 19th century tend to now be worth 1000 to 4000 times as much as they were worth in 1907, the $9.36 million result for the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon in 2021 does not seem excessive, from an historical perspective.

Curiously, the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon has fared better recently, in a financial sense, than the Stickney-Eliasberg-Miller 1804 silver dollar. In the same auction in 1907 in which this Brasher Doubloon realized $6200, that 1804 dollar realized $3600, 58% as much. In a Bowers & Merena auction on April 8, 1997, that 1804 dollar realized $1,815,000 a record auction price at the time for any coin. On December 17, 2020, this same Stickney-Eliasberg 1804 dollar realized $3,360,000, 933 times the price realized in June 1907, though 36% of the price that the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon realized about a month later. Relative prices for 1804 silver dollars have fallen over the last twenty years.

It is also important to take into consideration the actual physical characteristics of the items, not just their fame, rarity and assigned grades. Most of the people who think that the $9.36 million result was too much probably have not examined this Brasher Doubloon. It is a wonderful, gem quality coin, much higher in quality than I thought it would be, well struck and technically impressive. Those coin enthusiasts who are puzzled as to why this Brasher ‘New York Style’ Doubloon brought much more than other Brasher ‘New York Style’ Doubloons have realized at auction would have a better understanding of the value differences if they had examined all of the four ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons that have been auctioned since 2005.

On the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon, there are raised lines of various shapes, sizes and patterns all over the coin, which stem from die finishing work. These are both entertaining and fascinating. Some are very reminiscent of lines found on a few New York Copper patterns.

A longstanding theory is that Brasher was in league with one of the producers of New York Copper patterns, and may have been involved in the minting of some New York Coppers. Similarities in the finishes of dies used to mint Brasher Doubloons and of dies used to mint some New York Coppers are circumstantial evidence of a connection. In the Heritage catalogue for the FUN auction of January 2005 (their sale #360), the cataloguer declared that “All of the [New Jersey] Running Fox varieties are punchlinked with the Nova Eborac [New York] Coppers, the [NY] Excelsior Coppers, and the New York Style Brasher Doubloons.” It was thus asserted that some of the same punches were used in the preparation of dies for all those coins and patterns. I have not researched the technical aspects of this claim, and I am not commenting upon the veracity of it. Admittedly, I focus more on the quality and originality of coins and patterns than I do on identifying die characteristics.

The Stickney-Garrett-Partrick piece has been lightly to moderately dipped, though this is mild in contrast to the harsh dippings and/or severe cleanings that a substantial percentage of surviving 18th century gold coins have endured. In all likelihood, this Brasher Doubloon has never been polished, buffed, lacquered, filmed, varnished or waxed. A few hairlines are minor and are hardly noticeable.

Other than some imperfections on the border and edge, the eagle-side is nearly flawless. On the mountain/sun side, there are some light to medium contact marks, though these are not distracting. There are conflicting opinions as to which side constitutes the obverse, so I refer to one side as the eagle-side and the other as the mountain/sun side.

When viewed directly, this Brasher Doubloon exhibits a matte finish. When tilted at some angles under proper lighting, however, lustrous areas become richly animated. At other angles, one of the eagle’s wings glows. This Brasher Doubloon is mostly a green-gold color with russet tints. It appears stable and cool! While it received a star for eye appeal from NGC, a plus grade may have been more appropriate. The impressive strike, fascinating finish and lack of annoying imperfections altogether have a very positive impact. The border and edge indentations do not bother me much, though others may be more concerned about them. To responsibly discuss coins, it is important to consider both positive and negative aspects.

I have examined hundreds of relatively high grade British gold coins from past centuries, and the borders and edge of the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon are superior to the rims and edges of many of those. No coin expert will weigh positive and negative factors in precisely the same way as another coin expert. In my view, the positive aspects of this Brasher Doubloon are exceptionally admirable and the negative aspects are not very bothersome.

As a whole, the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon is very pleasing, more satisfying than the Perschke piece, though the Perschke piece has richer color. The PCGS graded MS-63 ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloon is often called the Perschke Brasher Doubloon as Walter Perschke owned it from July 1979 to January 2014. The presently discussed Stickney-Garrett-Partrick ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloon realized $725,000 in the Garrett I auction, which was conducted by Bowers & Ruddy in November 1979. Partrick had an agent bid for him. Walter Perschke told me in 2012 that he bid in person at the Rarcoa session of the Auction ’79 event on July 27, 1979. He paid $430,000 for his ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloon.

Rarcoa is a coin firm in the Chicago area that was then owned and operated by the late Ed Milas. In 1979, the Rarcoa cataloguer said that the Perschke Brasher Doubloon “grades a strong Choice About Uncirculated with virtually full original luster and hints of Prooflike brilliance in evidence.”

I thank Adam Crum for enabling me to closely inspect the Perschke ‘NY Style’ Brasher Doubloon in 2014. While one side merits a choice mint state grade, there is much noticeable friction on the other. Many coins that were called “Choice AU” in the past qualify for a MS62 grade in the present. Moreover, the Perschke Brasher Doubloon is livelier than the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon. The rich luster of the Perschke Brasher Doubloon notwithstanding , I personally grade the Perschke piece as MS62+ and the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick piece as MS65+. The Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon brought more than twice as much as the Perschke piece, $9,360,000 vs. $4,582,500, in Platinum Night sessions seven years apart. While market levels were higher in January 2014 than in January 2021, the $4,582,500 result was then a weak to moderate price for the Perschke Brasher Doubloon, and the $9.36 million result in January 2021 was very strong. In my view, the Stickney-Garrett-Partrick Brasher Doubloon is or should be worth 60% more, not twice as much.

It is a fact that only one of the seven surviving ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons has Brasher’s hallmark on the eagle’s chest rather than on a wing. That piece was NGC graded XF45 when it was auctioned for $2.99 million on January 12, 2005. It has since been graded AU50 by PCGS. “The Gold Rush Collection” arrived well after the consignment deadline in November 2004 and the staff at Heritage did not have as much time as usual to draw attention to this collection before the auction.

The Garrett Brasher Doubloon with 'EB' Punch on Chest (Images courtesy of Heritage)

The ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon was purchased by John Albanese from Steve Contursi late in 2011 for $7.2 million. In December 2011, it was sold to a client for $7.395 million. In 2015 or 2016, Albanese bought it again and sold it for an undisclosed amount to an investor through an intermediary.

It has been claimed that the states of the dies and of Brasher’s stamp demonstrate that the ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon was struck before any with the the punch on a wing. I am not convinced that this is so. It is curious that the ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon weighs more than the other six survivors, especially since it exhibits substantial wear. It is realistic to conclude that it weighed a few grains more than any of the other six did at the respective moment that each was struck.

It has been suggested that the ‘Punch on Chest’ is indicative of a different weight standard. Although the Jackman-Norweb (410.96 grains) and Smithsonian (409.8 grains) Brasher Doubloons have less wear than the ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon (411.43 grains), it is hard to precisely measure the extent of wear as the level of detail on each when struck is unknown. There is slight evidence that the ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon was deliberately heavier possibly because its planchet was deliberately not adjusted before striking.

Even if the ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher was deliberately heavier, it is unlikely that it was intended to be a higher denomination than the others. Some researchers have placed too much emphasis on the buy price of $15 that was published by the Bank of New York in 1784.

It is illogical to assume that this one published bid by the Bank of New York was paramount and unchanging. Besides, the offer of $15 by the Bank of New York was probably a function of market conditions in 1784, this bank’s holdings then of foreign gold coins and the bank’s business strategy. Various merchants, businessmen and silversmiths could have then valued circulated Spanish Doubloons at a level above $15. Also, relative values of Spanish Doubloons must have changed during the years that followed.

The price ratio of gold and silver varied in reality at different locations throughout the world in the same time frame, and varied in each location over time. Markets are not static. Government fixings of prices and exchange rates were often ignored or circumvented when they were inconsistent with market realities.

Also, before the middle of the 19th century, there were noticeable variances in the weights of the planchets used for silver and gold coinage at almost all of the relevant government mints in the world. In another words, particular deviations from specified weights were allowed at all mints, and actual deviations were sometimes larger in magnitude than allowances stated in laws, government regulations or mint polices. The differences in weight and estimated weight at ‘time of striking’ of the surviving Brasher Doubloons could all be within a range that was acceptable for Spanish Doubloons in business settings in New York during the 1780s.

Nevertheless, it is indisputable that the ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon commanded a significant premium on January 12, 2005, in the Heritage auction of “The Gold Rush Collection.” The NGC graded XF45 ‘Punch on Chest’ Brasher Doubloon brought $2,990,000 very soon after an NGC graded AU55 ‘Punch on Wing’ Brasher Doubloon realized $2,415,000.

The Gold Rush Brasher Doubloon with 'EB' Punch on Wing (Images courtesy of Heritage)

The fact that Brasher Doubloons are not offered often is one reason why coin enthusiasts become excited when they emerge. The $9.36 million result for the Garrett-Partrick ‘NY Style’ Brasher Doubloon is an auction record for a gold numismatic item. Why is it so valuable?

What are ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons?

Brasher Doubloons are not tokens or medals. They are either coins or patterns.

The design, engraving and minting of ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons required a great deal of work. It is unlikely that these would have been made for the sole purpose of trading them as coins for face value, $15 or $16. They are carefully and brilliantly designed pieces, which logically and artistically mix New York State and federal (United States) concepts of the time period.

Unlike New Jersey, Connecticut, Vermont and Massachusetts, the government of the State of New York never authorized an official coinage. There are, though, a considerable number of privately issued copper patterns for New York State coinage, stellar representatives of which were in the Partrick Collection.

Before the 20th century, it was not unusual for patterns to circulate. Some merchants and many curious consumers often accepted them. In the 18th century, there was a shortage of certain denominations of coins in North America, and many merchants were glad to accept patterns in trade. Nevertheless, patterns are different from coins.

If a round piece of metal circulates and is accepted as a payment, it is not necessarily a coin; it could be a pattern, a token, a medal, a counterfeit, or a foreign object used for barter. For example, in many instances a silver medal was accepted as payment by a seller who could estimate or thought he could estimate the amount of silver in the medal. In the 18th century and in the early 19th century in North America, merchants in large cities and/or near major ports were accustomed to receiving or being offered coins from various nations and other objects as payments.

Some patterns were promotional pieces and announcements to encourage people to become interested in proposals for or accepted designs of upcoming coins. Were Brasher Doubloons promotional pieces or announcements? Did they embody proposals for coinage by the State of New York or by the U.S. government?

I very much respect the scholars who maintain that ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons are coins, not patterns. If they were coins, however, I believe that there would have been a paper trail, or at least some documentation. Seeking attention from influential people by issuing patterns would be a smaller scale undertaking than encouraging a large number of businessmen to use new privately issued coins that were different from any gold coins that anyone had ever seen before!

Consumers and merchants would have to be notified and convinced. For ‘NY Style’ Brasher Doubloons to have been coins, many businessmen would have had to make a conscious decision to use Brasher Doubloons as coins rather than refuse them or have them melted. There would have been a need for aggressive marketing.

It is known that Brasher sought a contract for producing official copper coins for New York State. It would be logical to assume that he would have wanted to produce official silver and/or gold coins, too. After all, he was a widely regarded silversmith and goldsmith. Ten to twenty-five patterns struck in gold would certainly have attracted attention among government officials and politically influential businessmen, if they were distributed or traded in accordance with a carefully reasoned strategy.

If ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons were patterns, a small number of influential people would have been targeted. While there may not have been lobbying firms as such firms existed in later eras, there must have been lobbyists and other private citizens who involved themselves in legislative processes. It would have been legal for Brasher to hand a Brasher Doubloon to an influential private citizen who knew elected officials. This would not have been a bribe.

If ‘NY Style’ Brasher Doubloons were intended to be coins, then Brasher would have been compelled to make a large number of people aware of them and accepting of them. This would have been a daunting task. He would have needed to post announcements, place advertisements and/or encourage business people to mention them in letters and documents.

Most merchants who accepted gold coins in North America during the 18th century were familiar with government-issued gold coins that were ‘regulated’ by silversmiths, yet would not have thought about gold coins being privately issued. Although the idea of privately issuing gold coins would not have been thought of as wrong, there was not then a tradition of privately issued gold coins. Almost all communities, including business communities, have customs and other rules that gradually evolve.

Before minting them, Brasher must have known that ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons were just too different from the gold coins that circulated in the U.S. during the 1780s to be widely accepted as coins. Privately issued gold coins with an original and novel design would have been met with resistance or would have been avoided, regardless of the credibility of the issuer.

I conclude that ‘New York Style’ Brasher Doubloons were patterns that were distributed to resourceful individuals who could realistically influence legislative or other political processes. Even if Brasher figured that it was unlikely that he would secure a coinage contract from New York State or from the federal government, he could enhance his own influence and prestige by distributing Brasher Doubloons to selected individuals.

Copyright ©2021 Greg Reynolds

Insightful10@gmail.com

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Source: Greg Reynolds

Related Stories (powered by Greysheet News)

View all news

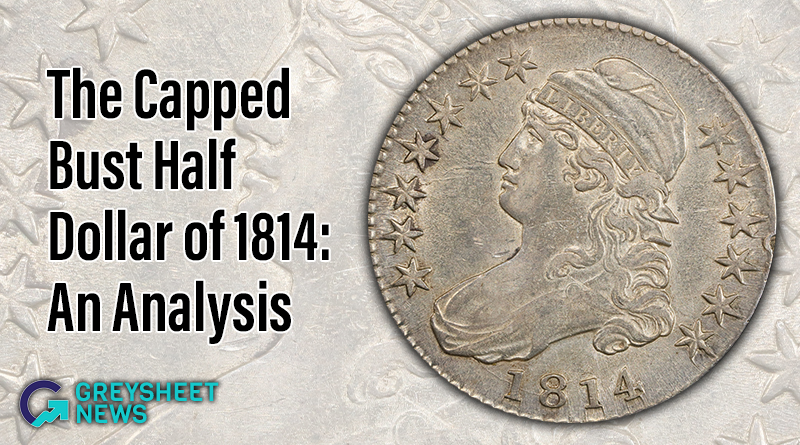

In this article Greg Reynolds analyzes the 1814 Capped Bust Half Dollar.

The Lusk set of Draped Bust quarters brought strong results.

The 1889-CC is the second scarcest business strike in the series.

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments