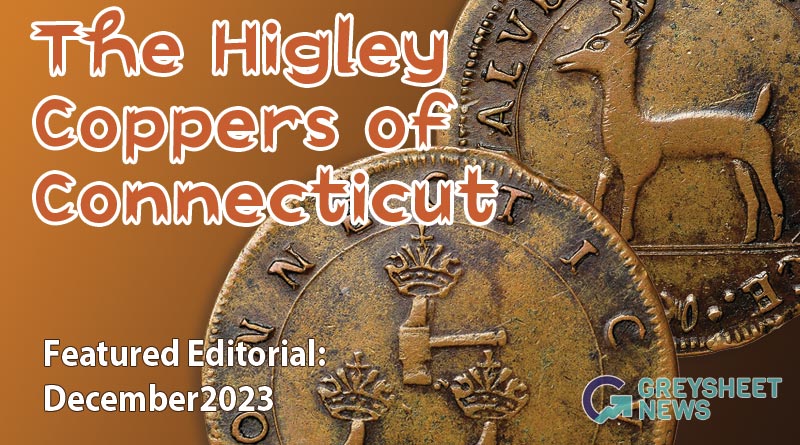

Introduction to Higley Copper Coins of Connecticut

Widely mis-understood in numismatic references, some collectors have missed out on one of the most exciting and important areas of coinage in the Americas.

Copper coins fairly attributed to the Higley family were minted in Connecticut in the late 1730s and maybe during the early 1840s. They circulated to a substantial extent and were almost certainly accepted on par with British halfpennies, the standard for copper coins in the 1700s in British colonies and many other places. As accepted reference materials tend to present Higley Coppers in a complicated or confusing manner, some collectors have missed out on one of the most exciting and important areas of coinage in the Americas.

With my classification system, the two major design types and five true subtypes may be easily remembered, and each Higley Copper may be categorized without the need for a reference book or a technical article. Moreover, I realize that it is not practical for most collectors to acquire representatives of all five true subtypes. It is free to learn about Higley Coppers and to view a few. They appear in auctions almost every year, and there are a substantial number in museums.

While die pairings are understandably important to researchers, there is not a good reason for every coin enthusiast to learn about all fifteen or sixteen die pairings of Higleys that have been documented. A point here is that collectors may easily learn about and enjoy these fascinating coins, without being bogged down with information about minor variations.

After spending a few minutes learning my classification system, and researching some auction records, an interested buyer may think about selecting two to four Higley Coppers, as they become available, to represent this series in a collection. It makes sense to focus on NGC or PCGS certified Higley Coppers and to hire a consultant who is independent of auction firms. Some collectors care a great deal about the physical characteristics of their coins, while other collectors are more interested in historical aspects.

Higley Coppers are true coins and not tokens. This is not because there is generally a stated denomination of three pence on each, with the Roman numeral three or with words, THREE PENCE. Some historians wrongly imply that this three pence denomination was misleading or intended to mislead. Residents of Connecticut were then very much aware that a Higley Copper was not worth three pence in the British system.

I theorize that illiterate or unknowledgeable people in Connecticut would then have known that Higley Coppers were intended to trade on par with British halfpennies, the standard small denomination coin in much of North America during the eighteenth century. A stated denomination or lack thereof did not matter in a financial sense.

The true denomination of a Copper, that of a British halfpenny, was obvious enough to people who spent Higley Coppers during the 1700s. The concept of a penny in the 1700s is much different from the meaning of a one cent coin in the present. Also, each Higley Copper usually measures around 1.125 inches in diameter, considerably wider than a current U.S. quarter, which is 0.955 inch in diameter.

In British colonies in North America, British monetary terms were deliberately twisted and redefined in a multitude of ways. During much of the eighteenth century, a penny, a shilling, and other British terms were defined differently in different areas. For political and not logical reasons, most such definitions were inconsistent with the official definitions emanating from London.

In the 1700s, merchants and active consumers were familiar with the coins and standard denominations that were used in everyday commerce. The British halfpenny, a copper coin, was the standard for small change, and the monetary system of the Spanish Empire constituted the standard for silver coins in the Americas. For political reasons, the monetary policies relating to everyday life were usually not clearly stated in legislation or local government directives in British colonies. People then knew that the stated denomination on Higley Coppers was deliberately false for political reasons; this was not a reason to question the honesty of the minters of Higley Coppers and was not a problem for most consumers.

Circumstantial evidence, the coin shortage on the East Coast, archaeological findings, and logic dictate that Higley Coppers circulated to a large extent as a general medium of exchange. Undoubtedly, most were worn heavily.

The reputation of Samuel Higley contributed to the acceptance of Higley Coppers as circulating coins. Samuel Higley was a widely regarded medical doctor, landowner, inventor, engineer and businessman. Furthermore, the Higley family owned a copper mine. Samuel was suited to plan or organize a mint. There is circumstantial evidence that some of his associates and at least one relative had pertinent skills. It is likely that the Higley family was the driving force behind these coins.

In an article of mine from 2013, I discussed and critically analyzed source materials regarding the Higley copper mine. As for the circumstances surrounding their minting, there is more logical and circumstantial evidence concerning Higley Coppers than there is regarding some of the Coppers minted during the 1780s. A few New York Coppers, for example, remain mysterious.

In his book, The Eagle That Is Forgotten (Wolfeboro NH: Bowers & Merena, 1988), researcher Joel Orosz indicates that, during the late 1700s, Pierre E. Du Simitiere owned seven Higley Coppers and made drawings of a few. Also, there is much evidence that collectors sought Higley Coppers during the 1850s.

Except for the unique, mysterious and questionable Wheele Goes Round piece, which is not really a coin, all known Higley Coppers feature the portrait of a deer on the obverse. The deer portrait was the trademark; the unchanging symbol for a Higley Copper. It is likely that many illiterate people and travelers would have recognized this deer motif and accepted Higley Coppers in transactions.

As the deer is on the obverse of all except the one anomalous Wheele Goes Round piece, the two primary design types are defined by central reverse elements: three hammers with crowns (H) or a broadaxe (X). All the Hammers (H) Higley Coppers are dated 1737. Surviving Axe (X) pieces are dated 1739 or have no date (ND).

H-3P-CT: The obverse legend reads THE · VALVE · OF · THREE · PENCE. · [3P] and CONNECTICVT · [CT] is on the reverse.

H-3P-IAGC: The same obverse of H-3P-CT, with the addition of a Roman numeral III, was matched with a reverse legend of I · AM · GOOD · COPPER. [IAGC] rather than CONNECTICVT.

H-Please-IAGC: On the obverse design that I refer to as Please, an interesting legend is featured: VALVE · ME · AS · YOU · PLEASE. The variety where the word “VALUE” is spelled as “VALVE” is of the same subtype. This is not an error. Before around 1925, it was common for a capital “U” to be represented by a capital “V” in public declarations. In the 1730s, either letter could have been fairly used. The H-Please-IAGC subtype includes more than one minor variety.

Axe (X) No Date or 1739: The Higleys with an axe all include the reverse legend: J · CUT · MY · WAY · THROUGH.

X-Please-ND: In coin collecting, the “ND” (no date) abbreviation means that the numerals of a year were deliberately omitted from the design or from particular dies.

X-Please-1739: This has the same general design as X-Please-ND, except that the date 1739 appears on the reverse.

The VALUE ME AS YOU PLEASE legend was intended to be humorous or satirical; there was no doubt that Higley Coppers would be accepted by many merchants as if they were British halfpennies, which tended to be in short supply. Colonists in New England needed coins for commerce.

Copyright ©2023 Greg Reynolds, Insightful10@gmail.com

Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions, HA.com.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Source: Greg Reynolds

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments