Price Discovery and the Role of Coin Price Guides

Where do these prices come from? and What role should these prices play in our decision processes?

Both online and in print, price guides are an ubiquitous part of the market for collectible coins. Coins, currency, tokens, and medals, from the beginnings of coinage in Classical Greece to the latest issues of the world’s mints, with prices often defined by grade and certification, there are few areas of numismatics that escape coverage by at least one price guide.

A coin collector here in the USA can easily be overwhelmed by the number of price guides covering our markets. Mass market or specialist, wholesale or retail, the combinations can yield a half-dozen different price estimates for the same coin, with often widely differing opinions. For our discussion, I would like to explore two questions: “Where do these prices come from?” and “What role should these prices play in our decision processes?”

Price Discovery

Much of the price structure in the U.S. coin market originates from bidding activity at the dealer level. Daily bids are posted on dealer trading networks including CDN Exchange for all common gold and silver type coins, modern issues, and coins that are typically traded in bulk. These prices can change from day to day, and even during the day, depending upon changes in related bullion price levels and the flow of orders by market makers in those issues. Dealers also place maintenance bids for issues that trade on a semi-regular basis—Type Coins in the most available grades, most 20th Century issues, and nearly all issues of Morgan and Peace Dollars except for the great rarities – signaling an interest in those issues if they become available. These prices often act as ‘indications’, or starting points for discussion when these coins are offered for sale. As we move up the rarity and price scales, auction prices realized become a more important piece of the pricing puzzle. However, extrapolating price levels from auction results can be tricky, especially if we look only at the numbers. Inconsistent grading can also give us some confusing results unless we understand which specific coin is tied to each result.

Finally, private sales play some part in price origination, though we must usually be highly cautious of privately reported results.

Price Guides

By their nature, price guides are generally backward-looking, as they report prices for sales that have already occurred. Wholesale-oriented price guides are published more frequently, the prices are usually more current, and they reflect recent bidding activity by market makers on the dealer exchanges. Retail-oriented price guides are published less frequently, often quarterly or annually, and include prices that reflect some unstated margin above the semi-secret wholesale price levels.

In the perfect world of price guides, only dealers would use wholesale-oriented guides, while collectors and other non-dealers would only use retail-oriented guides, providing for some agreed upon margin, a set bid-offer spread never to be violated. However, reality is that information is not restricted, and there really is no ‘retail’ price for most coins and currency, particularly so at the upper end of the market.

As I noted above, much of the price structure in the U.S. coin market originates from bidding activity at the dealer level. For coin prices that are set this way, retail prices will largely reflect the difference in mechanics between a wholesale and retail sale. If I have a group of 100 Saint-Gaudens $20s certified MS64, I may simply consult one of the dealer exchanges to find a current bid, maybe make a few telephone calls to other dealers who I know to be regular buyers in order to stretch the price a little, then ship the group in one lot for payment within a few days. In contrast, a collector looking for just one coin will want to pick the best one, may require a trade or delay in payment, and may have an extended option to return the coin, all of which will be reflected in higher retail prices. For markets where prices are set from the bid side, setting price guide levels at a set margin above active dealer bids is a reasonable approach. Collectors may then negotiate down from these levels.

1796 No Stars $2.50 Draped Bust Quarter Eagle (Image courtesy of Heritage Auctions)

Moving up the scales of rarity and price, the mechanics of a sale to a wholesale or retail buyer become very similar, and calling a price retail is no longer accurate. Prices realized from major auctions become more important indicators of price levels, and specialist input provides an advantage. Mint State Early Dollars, rare Early Half Eagles, and the finest known Liberty Seated and Barber coins are rarely offered in any quantity, and are almost never sold based upon a wholesale bid. For these coins, all prices are derived from the offer side. For markets which are set by the offer side, price guides should reflect prices realized from major auctions with good retail participation, or good faith estimates from known specialists. Understandably, prices set from the offer side are subject to a lot of interpretation and disagreement as price discovery events can be infrequent, much of the needed information may be private, and auction prices can sometimes provide mixed signals.

Anticipating the Next Price

Each transaction, whether public or private, is a price discovery event. Taken together, these price discoveries frame the market. Ideally, the role of a price guide is to anticipate these price discoveries, to provide a reasonable expectation of the next trading level for both buyer and seller. And for most of the coin market, including issues that trade with at least some frequency, historic trades are usually both numerous and recent enough to be good estimates of the next trade.

However, how do we price coins for which there is no recent trading record? How can we accurately anticipate the price for a coin that has been off the market for twenty or thirty years, or only traded privately, and for which there is no equal? It is here that the opinions of specialists carry the most weight. The finest known 1796 Draped Bust, No Stars Quarter Eagle is certified by PCGS as MS65 and last sold publicly in January 2008 at $1.725 million. The coin has traded privately twice since then, in 2013 to Oliver Jung, then in 2020 to a prominent California collection. Both trades were at prices above $2.5 million. Condition Census Early American Coins are an area that I know very well, and I am considered a specialist in these coins. Based upon my private information, the wholesale bid and retail offer price on this coin has been updated to $2.25 million at $2.7 million, which is a reasonable estimate of what this coin would bring if offered today in the public marketplace. However, this is somewhat misleading as there is no active bid to hit at $2.25 million, there is no coin on offer at $2.7 million, and the coin cannot be bought even with a bid of $3 million, as I have been told that it will not be sold in this collector’s lifetime.

Coin prices often seem to change reluctantly, as if every last price has a magnet attached to it. Occasionally, a truly landmark collection appears for public sale that shifts the market significantly, changing expectations. These collections typically include a number of finest knowns and great rarities that have been out of sight for an extended period of time. The series of sales from the Pogue Family Collection offered by Stack’s Bowers from May 2015 through March 2017, the February 2018 sale of the Admiral Collection of Coronet Eagles offered by Heritage Auctions, the upcoming sale of the Donald Partrick Colonial and Confederation Era Coppers, again by Heritage are examples of market-moving sales. When these are sold, they force a rewrite of the price guides, and anticipating the results beforehand can be difficult.

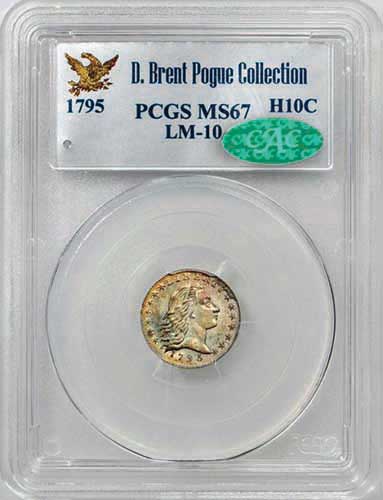

Price Discovery Under Fluid Grading Standards

PCGS was founded by a group of dealers led by David Hall in 1986, followed in 1987 by the founding of NGC led by John Albanese. These services were expected to standardize grading practices so that dealers and collectors could all read from the same playbook. Over time, standards slipped and grading numbers crept higher. In late 2007, John Albanese founded CAC in an attempt to standardize the output from PCGS and NGC. Once again, given time, disagreements appeared over what to expect from a CAC Approved coin. CAC’s judgement has been very good on gold coins, but subject to discussion on silver and early copper. Auction results occasionally display the market’s disagreement and price disparities occur, which, once again, make setting a guide price difficult. A good example is the three 1795 Flowing Hair Half Dimes certified as MS67 by PCGS, including coins from the Pogue, Knoxville, and Lull Collections. All three have sold recently in well bid public auctions, and all three appear to have sold to collectors. The Pogue and Lull coins are approved by CAC, while the Knoxville coin is not. The Pogue MS67 1795 half dime is the clear finest known, selling in 2004 at $161,000 (American Numismatic Rarities 11/2004:471) to Richard Burdick for the Pogue Family Collection, and offered with Pogue Part I in May 2015 where it sold to Oliver Jung at $176,250. I resold the Pogue MS67 privately in 2020, and it sold once again in November 2020 at GreatCollections for about $197,000.

The Knoxville coin sold in 2007 at $184,000 (Stack’s 1/2007:352), and was again offered in Part I of the Bob Simpson Collection (Heritage 9/2020:10038) selling at $132,000. A solid original Gem Mint State 1795 half dime, but with a hard scratch on Liberty’s forehead that kept it out of the CAC roster. Two months after Brent Pogue bought his MS67 at $161,000 the James W. Lull coin was sold by Bowers and Merena at $87,400 (1/2005:657). More recently, it was offered within the sale of the Larry Miller Collection as a PCGS-CAC MS67 (Stack’s Bowers 12/2020:1038) and brought a disappointing $120,000.

With these disparate results, how should we price MS67 1795 Half Dimes? As all three appear to have to have sold to collectors in well-bid public sales, these auction prices realized represent offer side prices. The Pogue coin is the standard bearer for PCGS-CAC, and an offer or retail guide price of $200,000 is warranted based upon its sale by GreatCollections. The Knoxville coin is the best non-CAC PCGS MS67, and its recent sale suggests a retail guide price of $130,000. As for the Lull coin, the recent sales result tells me that the market doesn’t agree with CAC’s assessment, so I ignore that coin for the purpose of PCGS-CAC guide pricing.

Summary

Price guides can be very useful tools in anticipating the next trading level. Knowing the sources of the numbers listed within the price guides will improve a user’s understanding of the market and should improve the process of price discovery between buyers and sellers. Learning when to deviate from these guidelines is key, especially when we are confronted with conflicting or dated market information.

Joseph O’Connor is the founder and principal of O’Connor Numismatics (OCNUMIS).

He can be reached via email at: info@ocnumis.com

Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions and Stack’s Bowers Galleries.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to CAC Rare Coin Market Review for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Joseph O'Connor

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments