United States Trade Dollars: Born of Need, Died from Greed

The United States Trade Dollar is an extremely interesting coin. No other American coin was created specifically for use outside of the United States, demonetized at one time, and re-monetized at a later date.

The actual creation of a Trade Dollar was intended to be an experiment, rather than a change in design. The Mexican 8 Reales was the dominant and preferred coin in Asia, and we wanted to have a coin that could compete and eventually become the coin that replaced it.

But by 1873, thoughts about silver coins were changing. President Ulysses S. Grant signed into law the Coinage Act of 1873, later called by detractors the “Crime of 1873,” due to the many and varied competing interests worldwide.

Judd-1002 Trade Dollar Pattern

The Coinage Act of 1873’s intent was to move the country from a bimetallic standard to the gold standard. That movement had started in Europe and affected the American political process. A standardized international currency was the chief aim but there were many problems in accomplishing that.

The Coinage Act of 1873 sought to remedy several issues. One of them was the fact that actual silver coins were becoming scarce. As the price of silver declined, a person could buy silver at a low price in the United States, then buy gold coins with the silver. Then they could sell the gold coins in Europe. They could then use the profits to buy even more silver back in the U.S. This was happening and now caused gold coins to also be hoarded. When that happened there was a growing disparity between the ratio of gold to silver coins.

Another component of the Coinage Act of 1873 was the prohibition, due to this legislation, of silver miners to be able to deliver quantities of raw silver to the Mint to be converted into silver coins. That element of this legislation initially proved to be a shock to the western U.S. mining interests. Greenbacks could still be redeemed for silver coins, but only up to a $5.00 limit. Now the western U.S. mining interests—mine owners, miners, farmers, and silver proponents—were fighting with the interests of the Eastern gold bankers establishment and their investors.

Amazonian Pattern Dollar

One of the most important developments to come out of the Coinage Act of 1873 was the creation of a United States Trade Dollar silver coin. John Jay Knox, who was the Deputy Comptroller of the Currency, had proposed the idea of a new silver coin for use in Asia. He held discussions with Louis Garnett, who had been both the San Francisco Mint’s Assayer and Treasurer. Garnett did not actually want a new legal tender silver coin. What he originally suggested was a disk made of silver or a stamped silver ingot, at a uniform weight and fineness. He wanted to call it a “silver union,” as opposed to it becoming yet another silver coin. These disks or ingots would be standardized and without any change or modification. The idea was to initially compete with the Mexican 8 Reales silver coin, which was the current preferred coin by Chinese merchants, and to later supplant it as the preferred medium of exchange in China and Japan.

Chinese and Asian merchants had, for decades, accepted the Mexican 8 Reales coin as the coin of choice. These merchants despised any changes to the design or weight and fineness, as they wouldn’t be certain that the change was authorized by the Mexican government or if they were looking at a counterfeit copy. But due to the new reign of Emperor Maximilian, a portrait of the new Emperor was now added and the 8 Reales coin was modified from the old design. These Asian merchants now were rejecting the Mexican 8 Reales silver coins all across the Orient. This provided a great opportunity for a new coin to become the primary coin to circulate in Asia.

During 1872 the U.S. Mint, under the direction of Chief Engraver William Barber, struck numerous pattern coins in anticipation of passage of this coinage bill and the need for a commercial dollar or trade dollar coin. Prior to the legislation being signed into law, the denomination was changed from “Commercial Dollar” to “Trade Dollar”

1872 "Commercial" Pattern Dollar

Bailey, Banks, and Biddle, the jewelers and silversmiths headquartered in Philadelphia at that time were also asked to create some possible designs as well. But the Mint and the Secretary of the Treasury preferred the designs that Barber had created.

The final approved design featured Miss Liberty sitting on bales of the products of commerce—grain, cotton, etc.—with wheat stalks behind her. In her right hand is an olive branch, representing peace, while in her left hand is a scroll with the word “LIBERTY” inscribed upon it. Thirteen six-pointed stars adorn the upper periphery while the date is below.

1873 Pattern Trade Dollar

The reverse depicts the Bald Eagle as required, but interestingly, she holds 3 arrows in her right talon and an olive branch in her left. On prior Seated Liberty coinage and Bust coinage, the arrows are in the eagle’s left talon and the olive branch in the right. Why William Barber changed that tradition is unknown. However, the arrows were in the right talon if one looks at the very early Draped Bust coinage with the Heraldic Eagle reverse.

Above the eagle is a scroll with “E PLURIBUS UNUM” on it with “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA” on the upper periphery and “TRADE DOLLAR” on the lower periphery. Underneath the eagle, to promote trade, is “420 GRAINS, 900 FINE.” That was added to advise the Asian merchants that this is what the American government had included for silver in these coins.

The Coinage Act of 1873 became law on February 12, 1873 but it was not until July of that year that the actual striking of a Trade Dollar coin commenced. Coins were struck at the Philadelphia, Carson City and San Francisco mints during that inaugural year.

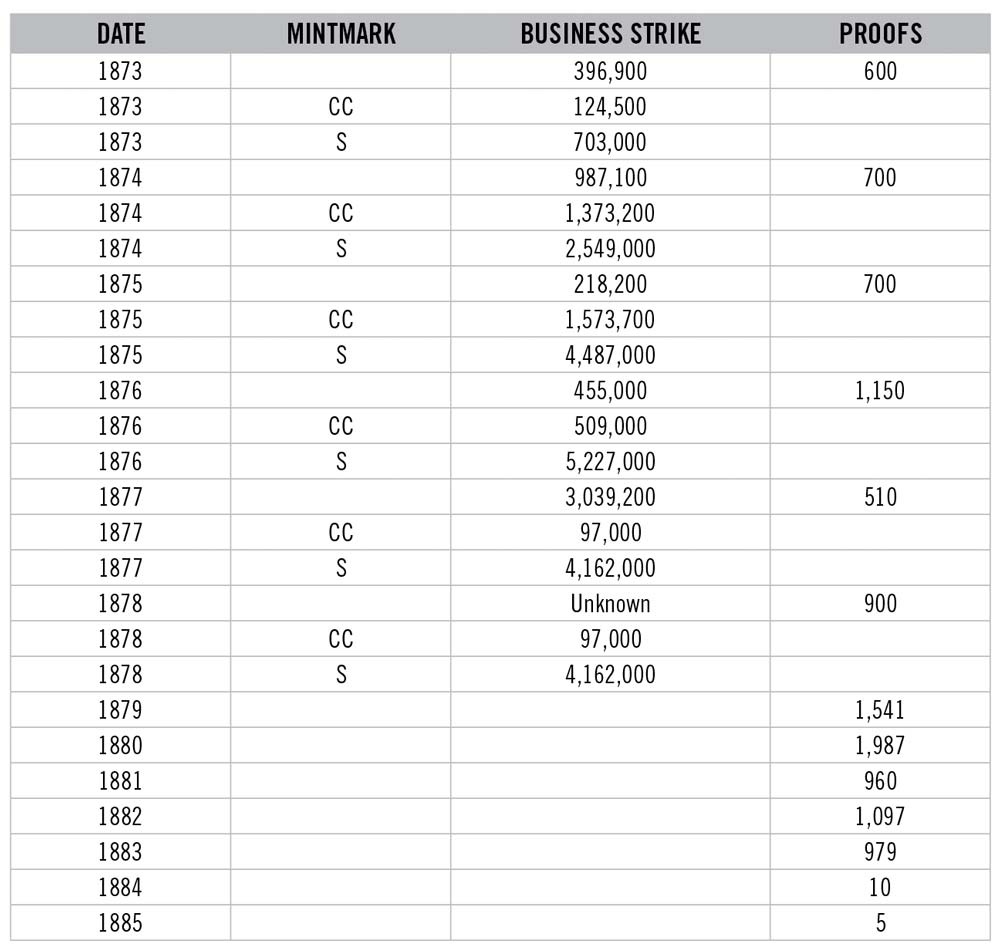

The mintages for all Trade Dollars is as follows:

Mintage chart of U.S. Trade Dollars

The Mint kept the number of strikings low, in order to determine how well

received these coins would be in China. When the first shipment of this new

coin arrived in China, official tests and complete assays were conducted by

the Chinese government. The results were that this new coin was exactly as

described and the Chinese Government issued an official proclamation that

the coin is “legal tender.”

In 1877, the American consul in Hong Kong provided a report to our Secretary of the Treasury on the reception for the U.S. Trade Dollar. The two leading banks that traded with foreign countries—the Oriental Bank and the Hong Kong Shanghai Banking Corporation stated:

“The United States Trade Dollar has been well-received in China and eagerly welcomed in these parts of the country when the true value of the coin is known. It is a legal tender at the ports of Foochow and Canton in China, and also at Saigon and Singapore. Although not legally current in this colony, it is anxiously sought after by the Chinese, and in the bazaars, it is seldom to be purchased.

If proof of the estimation in which the Trade Dollar is held in the south of China, we need only state that the bulk of the direct exchange business between San Francisco and Hong-Kong (which is very considerable) is done in this coin, the natives preferring it to the Mexican dollar!”

This was the resounding success of Trade Dollar in the Asian markets. It came at the time when Mexico was hurrying to make their silver coin acceptable to China again, as it once had been. But the American Trade Dollar beat them to the punch.

1873 Chop Marks with Exhibiting Extensive Chop Marks from Asian Trade

Mintages grew and more and more coins were being exported to Asia. But by 1874, some Trade Dollars began appearing in American commerce. By 1875, due to the value differences between the United States and China, a number of Trade Dollars were re-imported back to the United States.

Enterprising individuals would buy them at the actual silver value which was now under face value. Unscrupulous employers would buy them at under face and pay some of their employees with one or more Trade Dollars in their pay envelopes.

The experiment worked well as long as these coins were exported, and the price of silver remained stable. As more coins came back to the United States, the value dropped further. Some businesses accepted Trade Dollars so as not to offend their good customers, but they found that they could not deposit these coins at face value in their banks. The Mint stopped producing Trade Dollars for exportation to Asia by 1879 and thereafter only Proof Trade Dollars were struck for collectors.

Meanwhile, the proponents of a silver coinage tried to get the Coinage Act of 1873 repealed. The western mining interests and farmers banded together and with the support of western legislators, the Bland-Allison Act was passed in 1878. This Act provided that the Treasury Department must buy at least $2 million dollars’ worth every month, of newly-mined American silver to strike the new Morgan Silver Dollar coins. The Bland-Allison Act did not provide for any redemption of the Trade Dollars, then in circulation in the United States.

Even the on-going redemption of up to five Trade Dollars per person was not affected by the Bland-Allison Act. The only benefit to the Trade Dollar was the stabilization and then the increase in the price of silver.

But the existence of the Trade Dollar conflicted with the aims of the silver proponents of the new Morgan Dollars. The coins were legal tender for all debts, up to a sum of Five Dollars.

By 1876, Congress acted to demonetize the Trade Dollar’s tenuous legal tender status, even though the Mints were still striking these coins, exacerbating the problem since now banks and merchants could refuse these coins that no longer were considered legal tender. The proponents of Bland-Allison did not care about the imminent demise of the Trade Dollar coins. They only wanted more and more Morgan Dollars struck. They were blinded by the greed of the “deal” they were able to convert into law.

Beginning in 1879, only Proof coins were struck for collectors, and it is believed that the coins dated 1884 (mintage of 10) and 1885 (mintage of 5) may have been struck surreptitiously as it is unlikely the Mint would strike so few examples of any coins.

It wasn’t until the Coinage Act of 1965, which restricted the use of .900 fine silver in American dimes, quarters and half dollars that Trade Dollars were again monetized as legal tender silver coins.

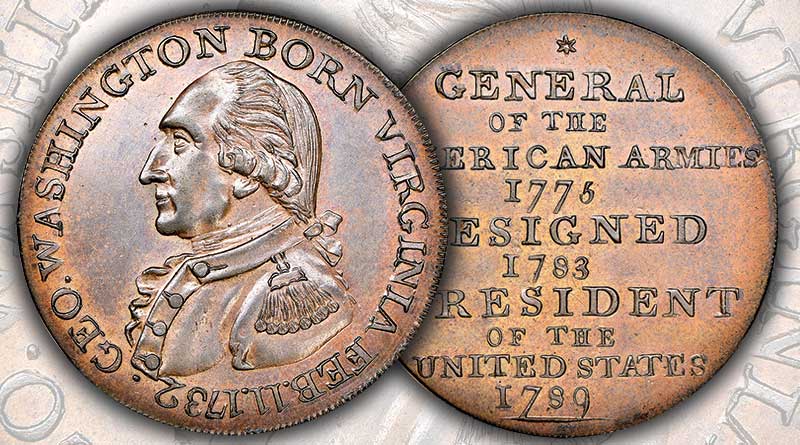

Many of the coins that circulated in China, even with the proclamation of their integrity publicized, were still tested by merchants who were wary of this coin. They would often strike the coin with a metal punch to make some of the underlying metal visible. This was a way for the coins to freely circulate there. But a number of those “chop-marked” coins were repatriated back to the United States. The coins with these chop-marks were unable to be redeemed as the Mint would only redeem unadulterated specimens.

For many years, collectors avoided these coins with those added foreign markings. When they became available, they were often heavily discounted out of necessity. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that a couple of the major grading services began to not only authenticate but also grade chop-marked Trade Dollars. Some of the chop marks themselves are well-known and can be traced to individual Asian merchants.

For a very long time, most U.S. coin collectors would obtain a single specimen of a Trade Dollar to be added to their Type Set. But that is no longer the case. This area of United States numismatics has been heavily collected over the last 20 years. Collecting these coins by date and mintmark is a popular pursuit today. Most issues are obtainable and affordable in varying grades, except for the 1884 and 1885 possibly surreptitious Proofs.

Between 1873 and 1883 there are only 23 different date and mintmark combinations. As has happened with other series, such as Large Cents, collecting these coins by obverse or reverse die variety increases the 23 different dates and mintmarks to only a total of 33 coins, which also includes a couple of rare varieties.

Today, collecting United States Trade Dollars, with or without chop-marks, by date and mintmark or even by die varieties can be as easy or complex or as expensive as you would like. This coin survived trips back and forth across the Pacific, having been shunned, demonetized, sold under face value, and finally re-monetized. It truly is a survivor having lasted exactly a century and a half—so far!

Images courtesy of Heritage Auctions, Stack's Bowers Galleries and Legend Auctions.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to The Greysheet for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Author: Michael Garofalo

Please sign in or register to leave a comment.

Your identity will be restricted to first name/last initial, or a user ID you create.

Comment

Comments