Reading Between the Lines: Inscriptions on our Coinage

By LIANNA SPURRIER, SPECIAL TO CPG® MARKET REVIEW

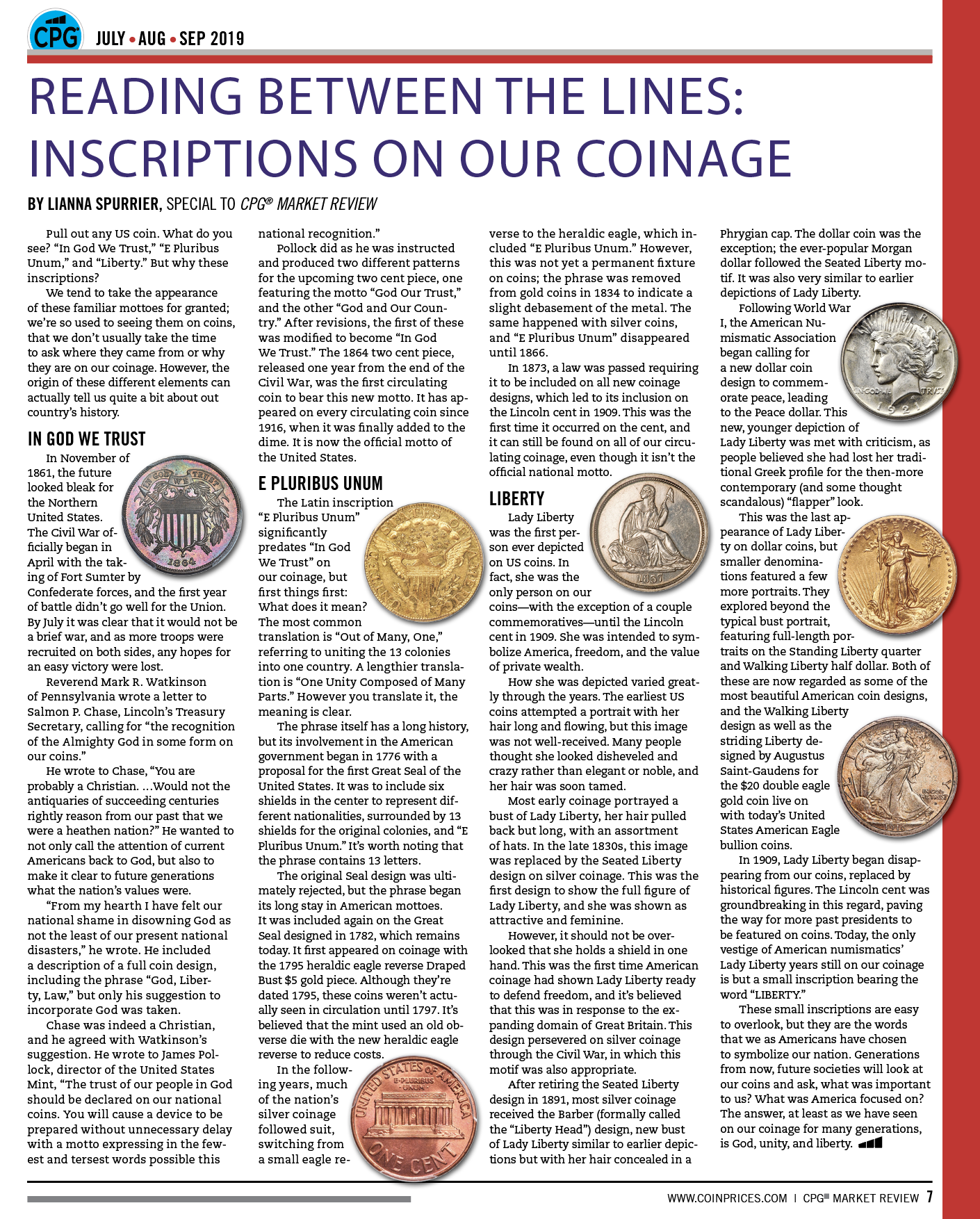

Pull out any US coin. What do you see? “In God We Trust,” “E Pluribus Unum,” and “Liberty.” But why these inscriptions?

We tend to take the appearance of these familiar mottoes for granted; we’re so used to seeing them on coins, that we don’t usually take the time to ask where they came from or why they are on our coinage. However, the origin of these different elements can actually tell us quite a bit about out country’s history.

In God We Trust

In November of 1861, the future looked bleak for the Northern United States. The Civil War officially began in April with the taking of Fort Sumter by Confederate forces, and the first year of battle didn’t go well for the Union. By July it was clear that it would not be a brief war, and as more troops were recruited on both sides, any hopes for an easy victory were lost.

Reverend Mark R. Watkinson of Pennsylvania wrote a letter to Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary, calling for “the recognition of the Almighty God in some form on our coins.”

He wrote to Chase, “You are probably a Christian. …Would not the antiquaries of succeeding centuries rightly reason from our past that we were a heathen nation?” He wanted to not only call the attention of current Americans back to God, but also to make it clear to future generations what the nation’s values were.

“From my hearth I have felt our national shame in disowning God as not the least of our present national disasters,” he wrote. He included a description of a full coin design, including the phrase “God, Liberty, Law,” but only his suggestion to incorporate God was taken.

Chase was indeed a Christian, and he agreed with Watkinson’s suggestion. He wrote to James Pollock, director of the United States Mint, “The trust of our people in God should be declared on our national coins. You will cause a device to be prepared without unnecessary delay with a motto expressing in the fewest and tersest words possible this national recognition.”

Pollock did as he was instructed and produced two different patterns for the upcoming two cent piece, one featuring the motto “God Our Trust,” and the other “God and Our Country.” After revisions, the first of these was modified to become “In God We Trust.” The 1864 two cent piece, released one year from the end of the Civil War, was the first circulating coin to bear this new motto. It has appeared on every circulating coin since 1916, when it was finally added to the dime. It is now the official motto of the United States.

E Pluribus Unum

The Latin inscription “E Pluribus Unum” significantly predates “In God We Trust” on our coinage, but first things first: What does it mean? The most common translation is “Out of Many, One,” referring to uniting the 13 colonies into one country. A lengthier translation is “One Unity Composed of Many Parts.” However you translate it, the meaning is clear.

The phrase itself has a long history, but its involvement in the American government began in 1776 with a proposal for the first Great Seal of the United States. It was to include six shields in the center to represent different nationalities, surrounded by 13 shields for the original colonies, and “E Pluribus Unum.” It’s worth noting that the phrase contains 13 letters.

The original Seal design was ultimately rejected, but the phrase began its long stay in American mottoes. It was included again on the Great Seal designed in 1782, which remains today. It first appeared on coinage with the 1795 heraldic eagle reverse Draped Bust $5 gold piece. Although they’re dated 1795, these coins weren’t actually seen in circulation until 1797. It’s believed that the mint used an old obverse die with the new heraldic eagle reverse to reduce costs.

In the following years, much of the nation’s silver coinage followed suit, switching from a small eagle reverse to the heraldic eagle, which included “E Pluribus Unum.” However, this was not yet a permanent fixture on coins; the phrase was removed from gold coins in 1834 to indicate a slight debasement of the metal. The same happened with silver coins, and “E Pluribus Unum” disappeared until 1866.

In 1873, a law was passed requiring it to be included on all new coinage designs, which led to its inclusion on the Lincoln cent in 1909. This was the first time it occurred on the cent, and it can still be found on all of our circulating coinage, even though it isn’t the official national motto.

Liberty

Lady Liberty was the first person ever depicted on US coins. In fact, she was the only person on our coins—with the exception of a couple commemoratives—until the Lincoln cent in 1909. She was intended to symbolize America, freedom, and the value of private wealth.

How she was depicted varied greatly through the years. The earliest US coins attempted a portrait with her hair long and flowing, but this image was not well-received. Many people thought she looked disheveled and crazy rather than elegant or noble, and her hair was soon tamed.

Most early coinage portrayed a bust of Lady Liberty, her hair pulled back but long, with an assortment of hats. In the late 1830s, this image was replaced by the Seated Liberty design on silver coinage. This was the first design to show the full figure of Lady Liberty, and she was shown as attractive and feminine.

However, it should not be overlooked that she holds a shield in one hand. This was the first time American coinage had shown Lady Liberty ready to defend freedom, and it’s believed that this was in response to the expanding domain of Great Britain. This design persevered on silver coinage through the Civil War, in which this motif was also appropriate.

After retiring the Seated Liberty design in 1891, most silver coinage received the Barber (formally called the “Liberty Head”) design, new bust of Lady Liberty similar to earlier depictions but with her hair concealed in a Phrygian cap. The dollar coin was the exception; the ever-popular Morgan dollar followed the Seated Liberty motif. It was also very similar to earlier depictions of Lady Liberty.

Following World War I, the American Numismatic Association began calling for a new dollar coin design to commemorate peace, leading to the Peace dollar. This new, younger depiction of Lady Liberty was met with criticism, as people believed she had lost her traditional Greek profile for the then-more contemporary (and some thought scandalous) “flapper” look.

This was the last appearance of Lady Liberty on dollar coins, but smaller denominations featured a few more portraits. They explored beyond the typical bust portrait, featuring full-length portraits on the Standing Liberty quarter and Walking Liberty half dollar. Both of these are now regarded as some of the most beautiful American coin designs, and the Walking Liberty design as well as the striding Liberty designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens for the $20 double eagle gold coin live on with today’s United States American Eagle bullion coins.

In 1909, Lady Liberty began disappearing from our coins, replaced by historical figures. The Lincoln cent was groundbreaking in this regard, paving the way for more past presidents to be featured on coins. Today, the only vestige of American numismatics’ Lady Liberty years still on our coinage is but a small inscription bearing the word “LIBERTY.”

These small inscriptions are easy to overlook, but they are the words that we as Americans have chosen to symbolize our nation. Generations from now, future societies will look at our coins and ask, what was important to us? What was America focused on? The answer, at least as we have seen on our coinage for many generations, is God, unity, and liberty.

Download the Greysheet app for access to pricing, news, events and your subscriptions.

Subscribe Now.

Subscribe to CPG© Coin & Currency Market Review for the industry's most respected pricing and to read more articles just like this.

Source: CDN Publishing